This essay is a new addition to my ongoing “Men Who Mow” series, where I feature ordinary people with acres of stories to tell. The original, “Luther’s Last Mowing,” introduces a stubborn, old caretaker who taught me almost everything about consistency and trust. Next, Chub’s story, “He’s Never Really Been Small,” is about noticing, about church-going, and about really good barbecue. I hope you enjoy this next one, and I hope it reminds you of someone you already know, or will come to know.

When he knocks on my door, I’m In the middle of a thousand things and cranky because the temperature in the house is well above 80 degrees, even though it’s only just now turned June.

He’s wearing his usual duds, all with the same patina, equal parts grass, dirt and diligence. The smell of vegetation and exhaust are mostly overpowered by that of sunscreen, visible in haphazard smears across his exposed skin and, I decide, in the pinkish stains on his attire.

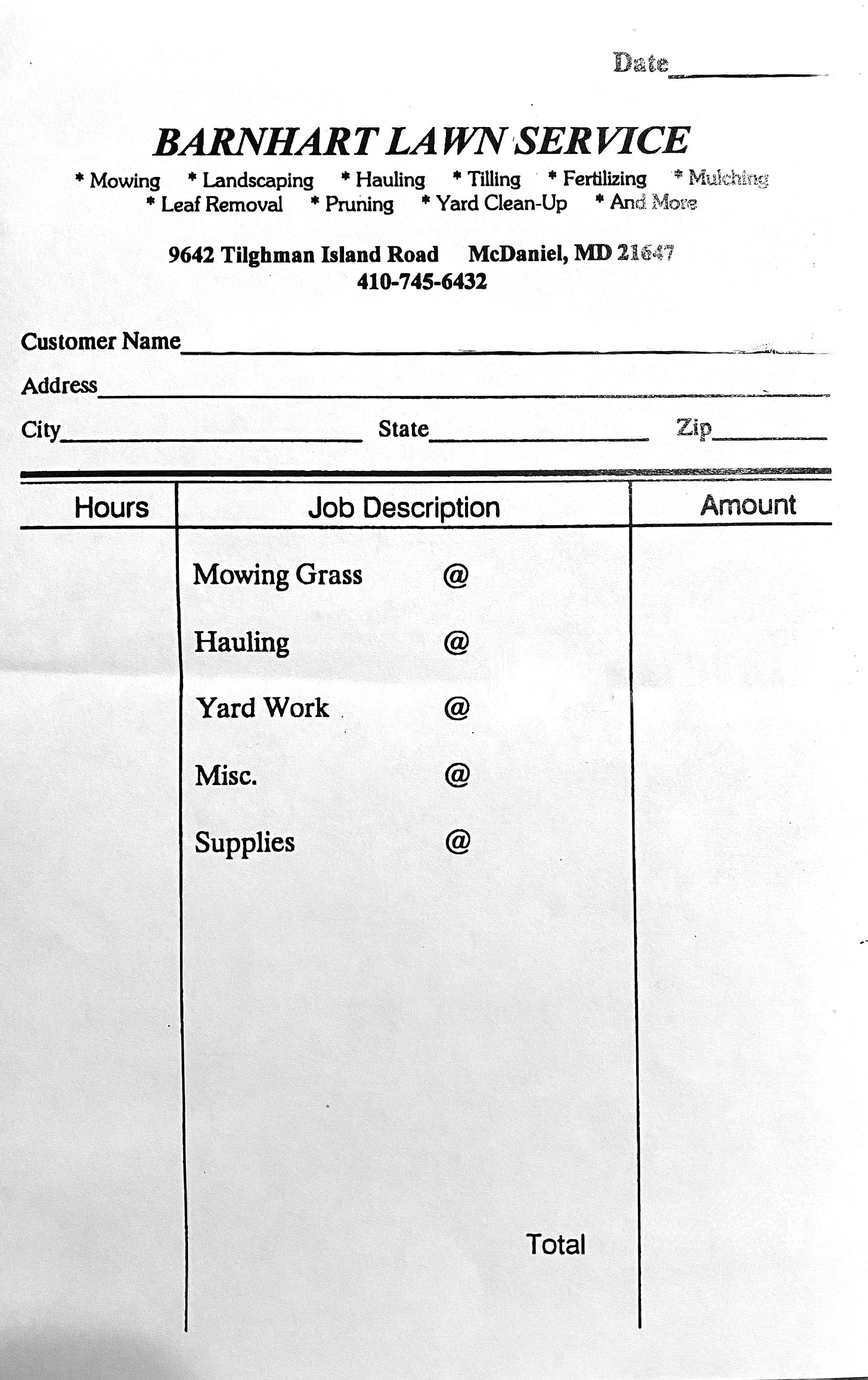

Arm outstretched to reach up the porch steps, he hands me an invoice, handwritten in cursive on a printed template, with his business credentials at the top: Barnhart Lawn Service: Mowing - Landscaping - Hauling - Tilling - Fertilizing - Mulching - Leaf Removal - Pruning - Yard Clean-Up - And More.

I comment on the weather, how I wish it weren’t quite so hot already, and his response catches me by surprise.

“Thing is,” he says, “it’s not hot where I am.”

I’ve no idea how to parse this. Does he keep his home thermostats set low? Is he working on waterfront properties with cooling breezes? I raise my eyebrows, tilt my head. He sees the confusion.

“Thing is, it’s snowing where I am. Nice and cold. Not hot at all. I picture it in my mind. It’s cold and there’s snow. I talked to a man, one of my customers, I talked to him, and soon he says ‘It’s not hot,’ and all like that. Turns out, he does what I do. In summer, it’s winter. In winter, it’s summer. I picture it in my mind. I flip the weather.”

That was the moment I knew Chris had a story that deserved to be told, a story I wanted to learn and would spend the next four months collecting.

I’ve known Chris for 15 years, and I knew his mother before that. We both served as board members for the small preschool and kindergarten my kids attended. A fierce advocate for children’s education, it seems her fire burned even hotter after Chris was born, the fourth of her five children.

In grade school, Chris got the extra support he needed because his mother drove him to the next town for speech therapy and alternative education classes. He remembers being the only white student in the program. He remembers competing in the Pinewood Derby as a Cub Scout, and as a runner in the county Special Olympics. At my request, he finds his medals, a silver and a gold, and brings them to show me. He has good memories from those years.

Things changed in middle school. That’s when he was mainstreamed and the teasing started, the poking, the joking, the bullying that followed him into high school.

“I got in trouble,” Chris admits, without apology. “I hit a kid. He teased me once too many times, and I decided I wanted no more bull. Thing was, I got lucky. The principal wasn’t there that day, so the vice principal, Mr. Smith, asked ‘What did I want to do for punishment? Did I want detention or to go work in the library?’ I picked the library, and after that, I kept going back. Turned out, I liked it there. They had me put books away, and all like that. And my senior year, I was a library aid, so I delivered things like movie projectors. I got out of class for volunteering, so I did a lot of it.

“Soon, it’s graduation time and they have the awards and the scholarships. I know I won’t get anything, but turns out, I hear my name. They call me on stage, and it’s this award, this senior award. I’m shocked as hell. Mr. Smith says it’s for all my volunteering. Thing was, they told me that to get the award I had to give a speech.”

A few days later, Chris spoke to a group of high school classmates and alumni at the local yacht club. It was the first and last time he stood before an audience like that. Reading a one-page address written by his mother, he remembers thanking a lot of people, including Mr. Smith. When he was done, Chris received a standing ovation.

Right after high school, he launched his lawn service business. At that point, he’d already been mowing lawns and doing yard work for four years. At 18, his parents helped him get a loan to buy a new John Deere riding mower. Since then, he has amassed a fleet of equipment that currently includes seven mowers, seven trailers, four pick-up trucks, and a 1985 Plymouth Horizon originally owned by his grandfather that he takes out for drives on Saturday afternoons.

All of Chris’s trucks are named. There’s the blue, 2011 GMC ¾-ton called The Beast, a 2011 of the same make and model named Workhorse, a 1989 Dodge Dakota known as The Pony Express, and his main vehicle, a 2017 GMC-350, that he calls Phoenix.

I quiz him about the last one.

“You know about the phoenix, right?” he asks. “It’s like me, coming up out of the ashes. And it’s because I like fire. When I was younger, and I was picked on, I got mad. Now, I can walk away. When I get mad, I get going. I go home and cuss up a storm. Out here, I only get to have two words. ‘Really?’ and ‘Mother fortune!’

‘Thing is, I’m happy at home. I can be myself. I don’t drink. I don’t smoke. I don’t do illegal drugs. But I’m not a joker. I don’t like jokes. My siblings like to joke. When they want something, they call me, but that’s it. One’s gone, the oldest, so there’s four of us left. There’s only one I trust. I’m kind of like a lone wolf.”

Alongside his lawn service business, Chris also salvages metal and tinkers with rebuilding old machines. He supports the work of our local community garden, and recently a customer hired him to offer valet parking for an afternoon memorial service. He told me he’d never done anything like that before. By his own admission, he also has a temper.

“A lot of times, at home, I’ll build a fire,” Chris explains. “Fire brings my stress down. Every three months, I light off my burn pile. I have to call to get a permit, so they know, the county, they know I’m burning. And the pile will burn all night. I just hope nobody sees it and comes over, because I don’t need that. I don’t need anybody telling me what I can’t do.”

When he needs a big infusion of stress relief, Chris heads west, across the state, to visit an aunt and uncle. Even the drive is relaxing, but once he arrives, that’s when he says his walls come down. He enjoys his aunt’s spaghetti and homemade sauce, the conversations at the table. And because it’s cheaper there, he goes shopping. Included in the haul from a recent trip: apples, which he’s turning into dumplings; two gallons of honey, for smearing on toast in summer, pouring on hot cereal in winter, and adding to dumplings. He feels like it helps with his allergies, too, and that it’s better for him than sugar. Diabetes runs in his family.

While he’s away, he also buys new shoes, three pairs—the ones he works in only last him about three months—socks, clothes, household supplies. He returns home all set.

“When I go to western Maryland, I send up the white flag,” Chris remarks.

“The white flag?” I repeat. “Meaning, you surrender?”

“I surrender,” he confirms. “Thing is, I’m anti-hug. But my relatives, they like hugging. So I surrender.”

I ask what’s wrong with hugs.

“Somebody hugged me once,” he says, his voice dropping a little. “I didn’t like it.”

Looking away from me, he continues, “I don’t like the first part of October either.” My mother died on October 1st. My father died on October 12th. My birthday is on the 11th. So, every October 13th, I start a new life.”

He pauses and seems to be collecting his thoughts.

“My mother was my protector,” he finally says. “One move against me, she’d go after you. And I protected her, too, when she needed me. I looked after her. For fourteen years, I took care of her. At the end, she couldn’t get out of bed. I kept a lot of secrets. A lot of secrets. Like a pine tree when the sap comes down. When my mother died in 2009, I lost my protection.”

With his unvarnished delivery and practical wisdom, every story Chris shares is like having a conversation with a beluga whale, or a patch of moss, or the moon. Now, he shrugs in the matter-of-fact manner I’ve come to expect.

“Main thing is, I’ve been bullied in the family and out of it. That’s the way life is. But look at me,” he says. “I’ve built my company from the scratch up. My parents taught me to work hard. A lot of people didn’t have the guts to do what I’ve done.”

It turns out you can know someone for a very long time without knowing anything at all.

~Elizabeth

Let’s chat in the comments. Have you had the chance to get to know someone like Chris? Did you learn anything unexpected? What stands out? I’m always delighted to hear what you’re thinking. If you’re not up for sharing publicly, you can always message me privately, and if that’s more than you can muster, please at least ding the heart button at the top of the page, so I know you have a pulse. 😅

Special thanks to Roe and Beth for their recent support! Every Chicken Scratch essay is rooted in the gifts of time and intention. I want it to remain free for everyone, regardless of means. If you are able to consider contributing, you will be encouraging more than just the effort of creating these pages.

Paid subscription options can be accessed here, and one-time contributions can be made here. Any amount is sincerely appreciated.

Less than two weeks to go for the U.S. Election: If you are eligible to vote, whether in-person or by mail, please do! Click here to find out more about how to do that in your state.

We should all be so fortunate to have a Chris, or more of those good folks, in our lives. They are bed rock solid, as dependable as a new day, have carved out a life for themselves by serving others, and have stories worth hearing and repeating. These are the people who restore our faith in humanity, some whom we see often and have no idea of their story. That's why it's worth telling and sharing. Thank you!

Living in a rural community on The Eastern Shore and working in outpatient rehab, I had the privilege of meeting and hearing the stories of "essential" members of my community. Their stories remain engraved within me, more so than the "celebrities" and "notables" I met or treated. They helped me to embrace authenticity in my daily interactions. I feel such gratitude...