Allow me to acquaint you with Luther Marshall, a man who became part of my history nearly 30 years ago. I think of him regularly. He was called to mind this recent time when my man-person and I watched a new film on Netflix with one of those as-it-should-be endings. It was the kind of movie that allows those of us on the brink of losing ourselves to cynicism to feel better about life, the universe, and everything.

You want the title, I know, but I’m not going to give it to you, lest I spoil some bit of its deliciousness. But, I will tell you this: Besides its universally poignant exploration of living, loving, and leaving, what I found most gratifying was its emphasis on the daily habits of the main character, right to the very end.

I met Luther in 1994, when we were invited by owners, Ann and Charlie Yonkers, to move our growing family to Pot Pie Farm. He was 79 years old and had been working at the property for 50 years. Kept on as caretaker through seven different owners, the farm was part of Luther’s DNA. He remembered more than most people had ever known about it. Also, he got things done, and you could set a clock by his routines. Luther was dependable, deliberate, inveterate.

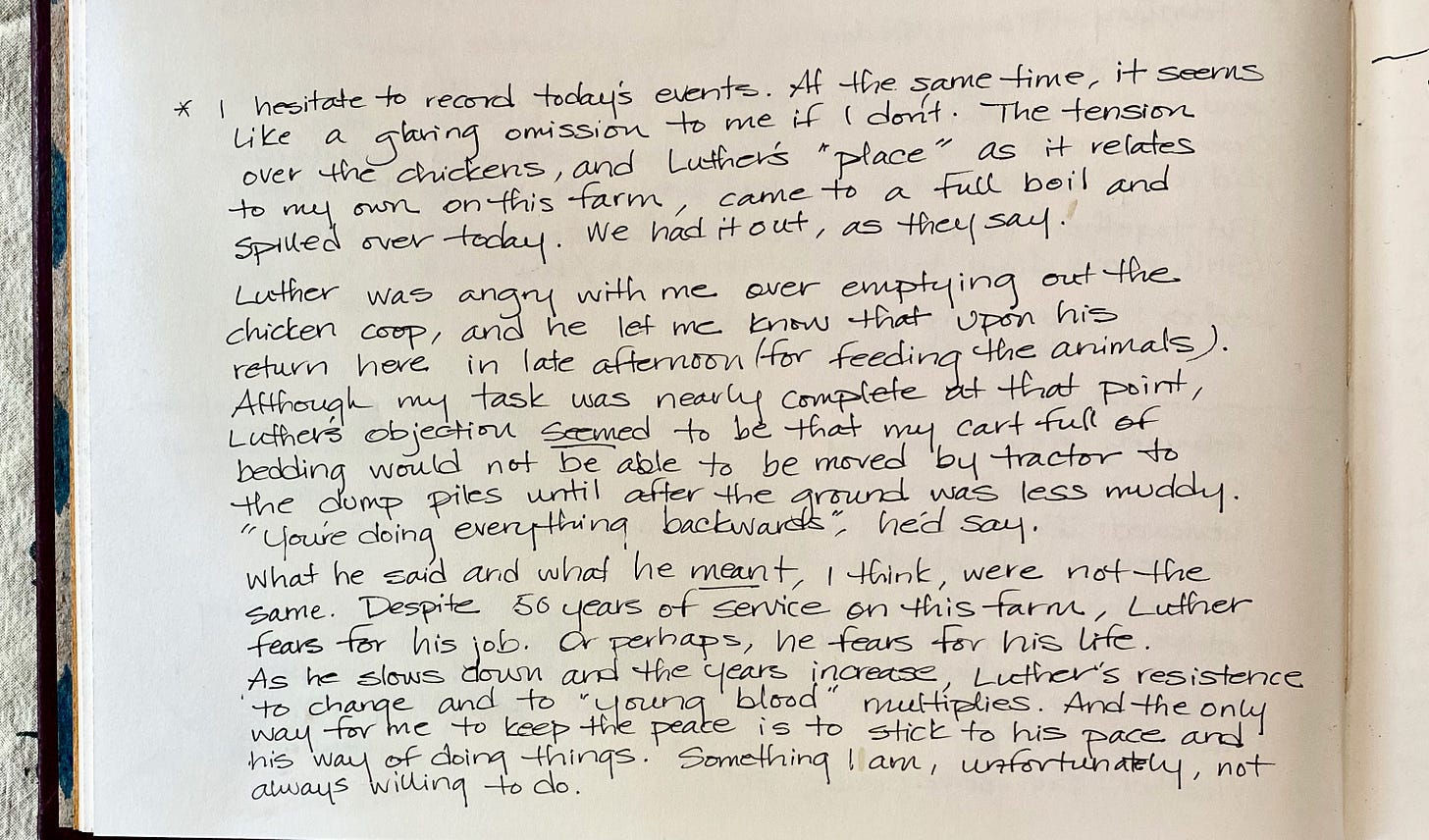

He did not love us. Not at first, anyway. Our arrival threatened his job security, or so he thought. We were young “come-heres.” We cramped his style just by taking up space on the farm. And, worst of all, as the one who interacted with him most frequently, I occasionally had the audacity to question his way of doing things.

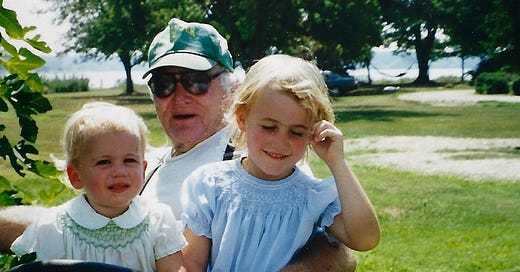

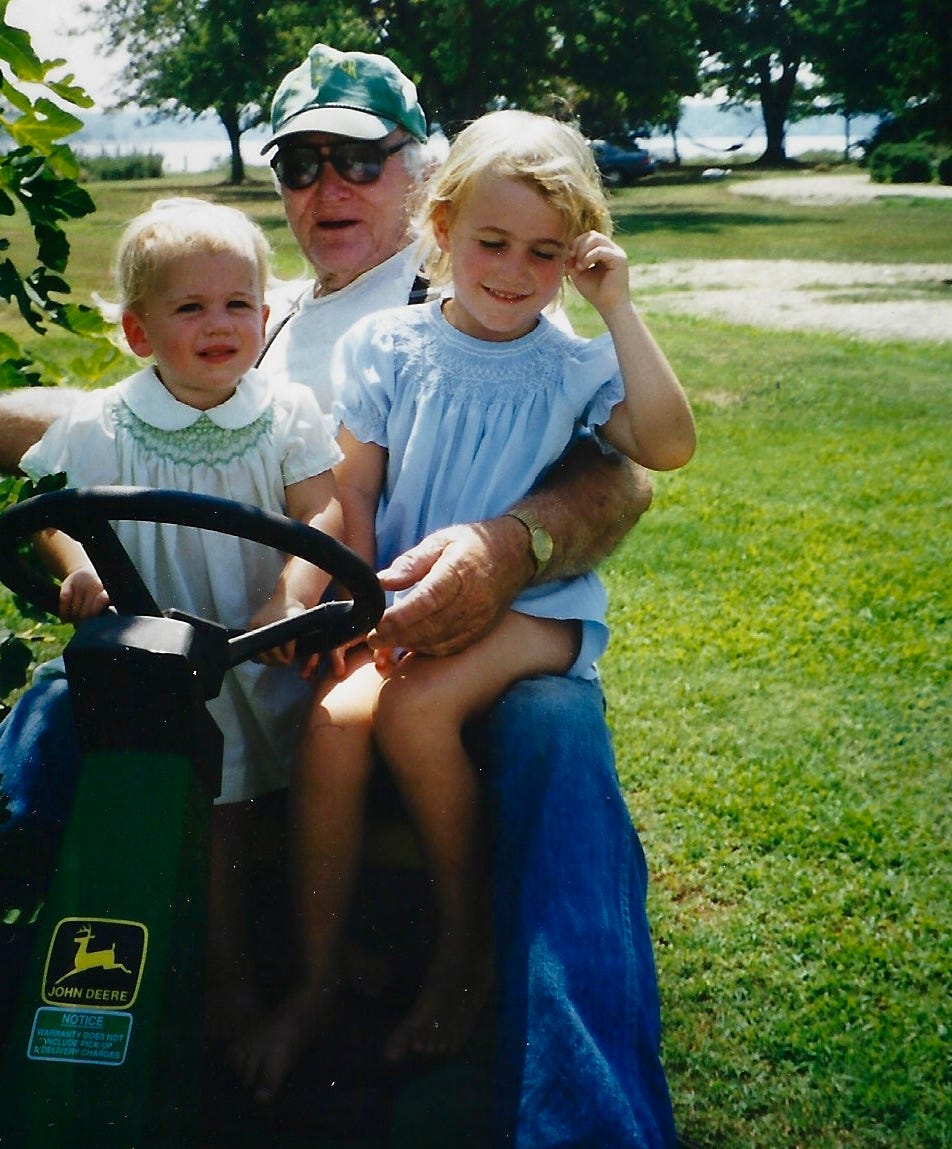

Thankfully, tension eventually gave way to trust. Luther adored our kids, who made their respective appearances after we moved in. In time, he came to see us as part of his team. We were good for each other, good to each other.

Each weekday morning, Luther arrived between 8:15 and 8:30. He climbed out of his Plymouth Reliant* and started right in on chores, tending the birds – ducks, chickens, pigeons - and the cantankerous pony.

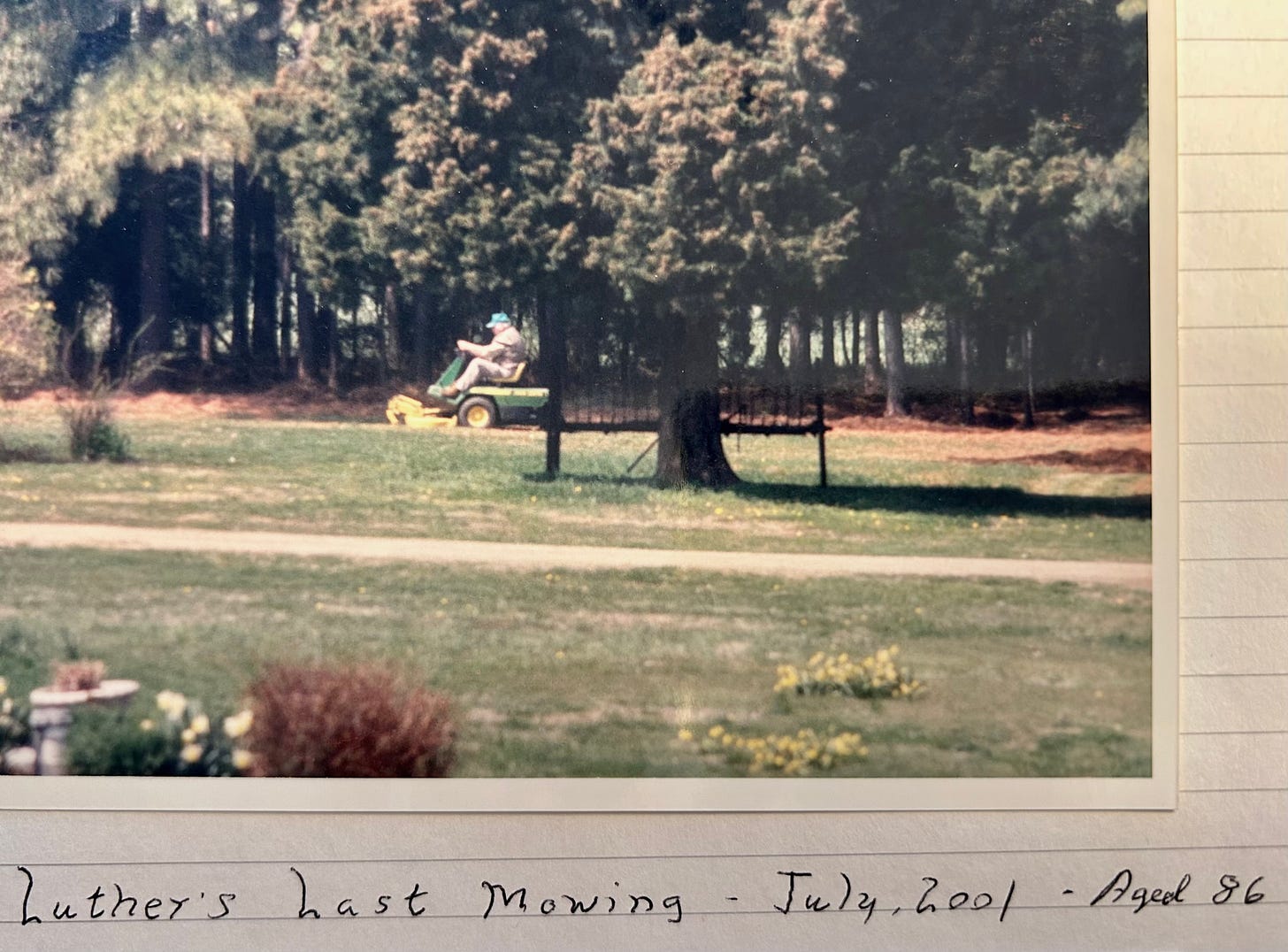

Next, when the season demanded, he fired up the mower. To manage the lawns on nearly 10 acres, a responsibility he took quite seriously, Luther spent the first half of every day on that machine. Spring through fall, hour after hour, he rode back and forth across the property, the drone of the trusty John Deere becoming the white noise of my farming days.

Luther’s routine turned into my own. I counted on him to roll down the driveway within the same 15-minute window every day. If I needed him for something, I could reliably predict where I might find him, based on the time. I anticipated, sometimes grumpily, the persistent sound of the mower. I knew, from the proximity and tonal shift, when he pulled alongside the enormous fig tree that flourished just a few steps from our back door. He’d put the engine in neutral, disengage the blades, and for a few blissful moments, sit still while he helped himself to the most delectable fruits. In the absence of a complete set of teeth, tender figs were easy for him to eat.

Luther’s small cottage was little more than a stone’s throw from the farm. He had outlived two wives and had no children. Of several siblings, only one lived nearby. He maintained just a few friendships and cared for Stubby, his dog. He spent a lot of time on his own. Given his age and the interlacing of our lives, I considered the likelihood that I might be among the first to spot a health calamity, or to react if he didn’t show up for work as expected.

When I noticed the mower at a standstill that day, it was mid-morning - too early for Luther to have already completed his rounds. Odd, I thought, but I went back to work. Minutes went by. The mower sat, running but not moving. It was way over on the other side of the farm, and I couldn’t make out much detail, so I set down my garden tools and started walking. First, it became clear that Luther wasn’t in the seat. Then, I spotted his body, contorted, lying in a shallow ditch beside the machine. That’s when I started running and shouting his name, terrified of what I was about to find.

Just as I approached, his head and torso rose up off the ground, then went prone again.

“Luther?!” I gasped.

“Damn trash!” he growled, shoving one arm back under the belly of the green beast.

He’d run over a rogue piece of baling twine which was now jammed up in the mower blades. He cursed and grunted as he wrestled the parts free, then sat up and waved the wad of frayed, orange nylon at me with a scowl.

“I thought you’d keeled over out here!” I admitted.

“Not yet,” he said with a wry smile.

With some effort, he stood, took up his position on the yellow seat and wrapped one enormous hand around the steering wheel while the other shifted the mower into gear.

Routines are my sweet spot. What I forfeit in spontaneity I recover in dependability. For the most part, I show up when I say I will, I keep to similar physical and philosophical paths, and I move methodically through almost everything. This is not to say I am unadaptable. Anyone who has ever parented, or farmed, or - heck, lived! – understands the futility of expecting predictability at every turn. But, I am generally content to find my surprises between the folds of the quotidian.

Seven years after our arrival, Luther’s doctor told him he needed to stop mowing.** A few years after that, on May 30th, two months to the day before he turned 90, he died at his home on Marshall Lane. Our older daughter stood up, unexpectedly, to speak at his funeral.

“Luther was my friend,” she began.

He was one of the best routines I’ve ever had.

~Elizabeth

*Full disclosure: I’m not a car person. I’m conjuring the make and model out of wispy mental remnants, but you get the idea.

**Special thanks to Charlie Yonkers for providing some of the historical details I needed to write a more complete story, and for the photo from his journal of Luther’s last mowing.

This issue of "Chicken Scratch" is why I love it. Elizabeth nails a quality-of-life issue that applies to all readers. Her recognition of Luther Marshall's habits, characteristics, and contributions are not only accurate and true, but emblems of things we know we need more of in life. Take one: reliability. Elizabeth signals his punctuality and consistency appropriately, but only alludes to his holistic fulfillment of the word "caretaker." The responsibilities he took on were not mowing or feeding chickens only. Rather they included a myriad of unspecified matters of care for a place and its people. When they grew to include Elizabeth's and Jim's daughters, well, nothing was ever said, but Luther unspokenly included them and their safety into his "job," and we could all rely on it.

One time, of unforgettable import, we sat one afternoon on a summer porch with his local best friend Littleton Grace, and Adam, our son who had recently graduated from college. The subject of Franklin Roosevelt came up, and Luther began to talk about the Great Depression. He talked about how down here in the Bay Hundred of Talbot County, Maryland, before the bridge, it was a backwater lacking in any visibility. Work of any kind was hard to find, and food and survival were at a premium. But Luther said "We knew President Roosevelt cared about us. He was the first and only president who paid attention to people like us. We felt it, and knew we could count on him." Littleton, a black man, agreed. "When he (FDR) talked on the radio, you knew he had us low class people in mind." In his latest years, Luther and Littleton lived on Social Security checks. Talk about a history lesson.

Luther taught us all so many life skills, not by preaching, but by example. One was to put your tools back. Many a task was begun, and then interrupted...leaving behind the shovel, screwdriver, or weedwhacker...soon to be forgotten, and then spending hours or days looking for the damn thing..."where on earth is...?" Luther always put his tools away, reliably, even if for a few hours. That's another reason to think about Luther almost every day.... Good goin', Chicken Scratch.

I may have to change my reading to the evening of publication where I can properly emote in the privacy of my home. My co-workers I am quite sure, do not understand the unexplained and unapologetic laughter or random face leaking episodes that have become a symptom of my weekly reading.

I thank you for these emotional outlets my friend.