Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?

That depends a good deal on where you want to get to.

I don't much care where —

Then it doesn't matter which way you go.

― Lewis Carroll, Alice in Wonderland

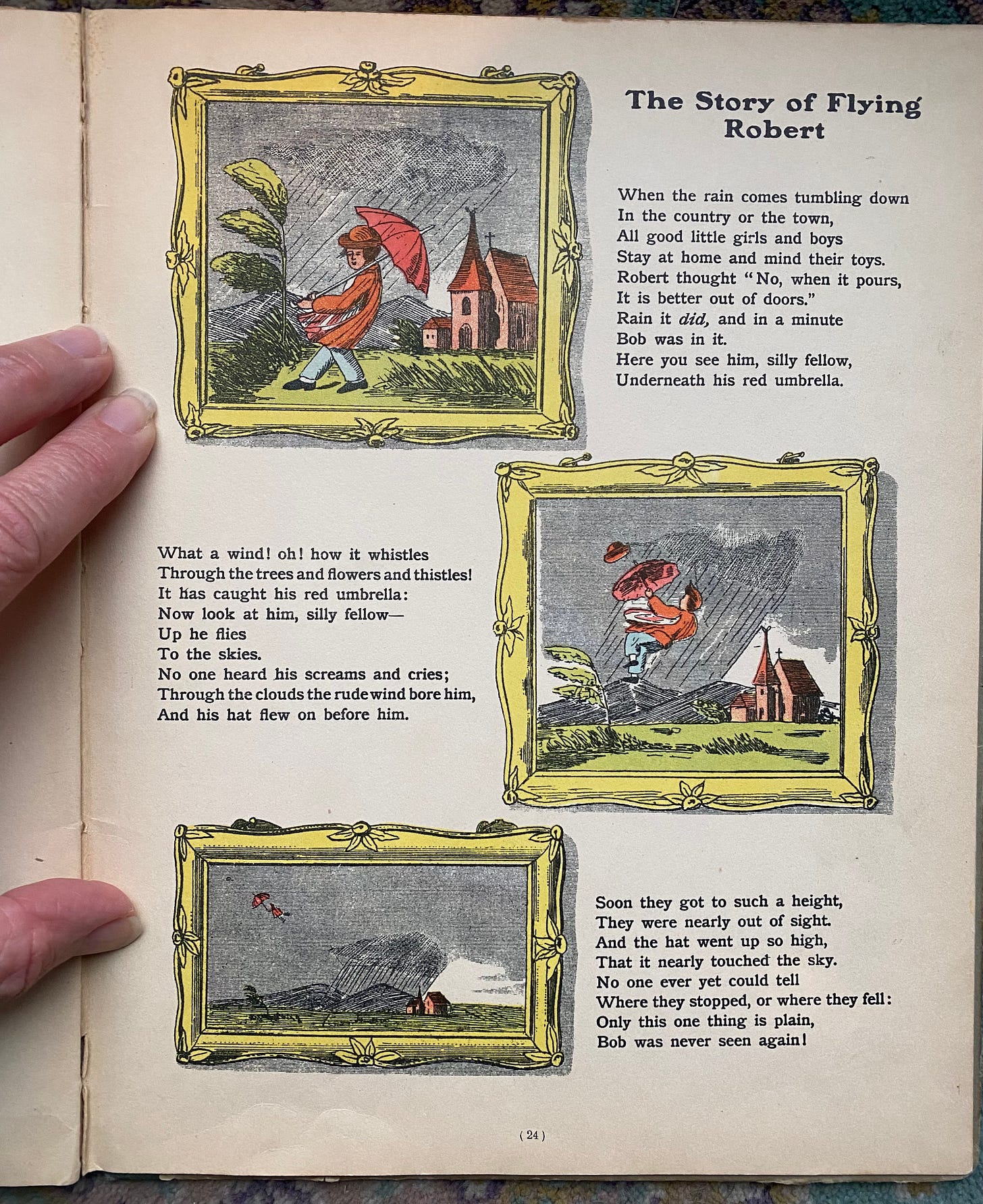

Last week, I dove into a deep exploration of Struwwelpeter by Heinrich Hoffman, a storybook that influenced both my and my mother’s childhoods. It features terrifying tales and shocking illustrations of what happens to disobedient boys and girls. Throughout its few pages, recalcitrant children lose love, life, and limb, consequences that seem disproportionate to their transgressions and incompatible with the cheerful colors and lyrical verses that accompany them.

Too socially irresponsible and politically incorrect for modern library shelves, the book has, nonetheless, held enduring interest for close to 200 years. Some see it as satire, its bright illustrations and rhyming text a mockery of the pedagogical children’s books of its day. That’s certainly part of its allure. But I think it’s also more than that.

Consider a time, recent or past, when someone told you what to think or how to behave. For me, whether the directive comes from someone I respect or from a sanctimonious blockhead, I’m apt to bristle. I may keep my sentiments better hidden from the former, but the feeling is still there.

“Don’t tell me what to do!” it glowers.

I believe it is precisely this which draws us to Struwwelpeter. It shows us how to resist convention, tackle our own problems, and take risks, even when the ramifications may be unfavorable.

Many of us readers came of age in a time when a cadre of youngsters could spend hours horsing around outside, without ever checking in. “Be home in time for dinner!” our parents said, as they ushered us out the door. Unlike the proverbial grandpa, who walked to school uphill both ways, this was no trope. This was the beautiful reality of our childhood.

I remember those long, lazy days spent exploring the neighborhood with my friends, and I remember how completely unperturbed the adults were at our extended absences. They may have held quiet concerns of their own, but it was such an accepted part of raising children that I never knew anyone whose parents resisted the practice.

In How To Raise An Adult, author Julie Lythcott-Haims identifies key societal shifts that gave rise to the age of over-parenting. Increasing numbers of women in the workforce mixed with elevated fears of abduction and injury spawned an epoch of parents erring on the side of caution. This was when play became something to organize, supervise, and sanitize. This was when play lost its imagination. A swarm of parental helicopters took flight, and they’ve been hovering over us ever since.

When my daughters were small, their great good fortune was that their playground was the 10-acre property where we lived and farmed. As orphans, or faeries, or circus performers, they roamed its outbuildings, its grassy terrain, its woody thickets and watery edges.

Like film-makers producing an epic adventure, they devised elaborate stories and games, tucking into forts cobbled together with bushes, and branches, and baby blankets. From a collection of silk scarves and fabric remnants, they fashioned whimsical worlds complete with the clothes needed to play their parts.

The older one, wielding her seniority like a weapon, insisted that the younger one retrieve anything they didn’t already have. I’d catch glimpses of her sprinting back and forth across the wide-open field, nimble little legs disappearing into the house and running out again, miniature arms filled with provisions and the hope that her sister would, at last, be satisfied.

The big barn offered shade in the summer, shelter in winter, and a change of scenery from our wee cottage when the rain just wouldn’t stop falling. I was so relieved when they could finally slide its massive doors open without my help. One less responsibility. There were animals to nurture, vegetables to tend, always a little too much to do, and never quite enough of me to go around.

The farm was idyllic but not without hazards. With an unfenced, in-ground pool and naturally occurring creek waters on three sides, there was seldom a time I wasn’t on alert for disaster. We still talk about the day my husband came home to find me sobbing and panic-stricken on the floor. Exhaustion coupled with the magnitude of keeping our kids safe, while still doing my job, seemed an impossibility.

I was 100 percent sure something was going to go terribly wrong. It was a very, very long time before my heart stopped lurching into my throat each time our young explorers were out of sight and didn’t respond quite quickly enough to the ringing of the brass ship’s bell that hung on our back porch, or, if all else failed, my high-pitched, two-finger whistle.

We kept at it. We figured things out.

After a deeply satisfying tenure spanning more than a decade, we finally pulled up stakes and headed to a house of our own, in town. For our daughters, it was the end of an unparalleled time of freedom, during which trial, error, and the laws of nature taught them some of the most important lessons of their lives.

In 2014, exactly seven years after we left the farm, I came across “The Overprotected Kid,” a thorough article in The Atlantic by Hanna Rosin. The story features a playground in Wales called the Land (it still exists) where children follow their exploratory instincts with little to no adult interference, turning flips on old mattresses, toppling stacks of wooden pallets, even starting fires. It felt as though it was written just for me, validating everything my gut told me was true about my kids’ childhoods and reawakening a most profound gratitude.

Our daughters, now adults, still embody the essence of those years on those acres. Like Struwwelpeter and his compatriots, they’re none too keen on being told what to do. They’re apt to question authority and aren’t afraid of taking risks. They’re inquisitive, unconventional, and seem to leave lasting impressions on those they meet. And the place that breathed life into their imaginations? Though we are physically separated from it, that land and its wisdom continues to hold us all.

~Elizabeth

Yes! I think about this a lot. I grew up in Urbana, Illinois, a university town of about 100,000, in the 1960s and '70s. Both parents worked and we had keys for when we got home before they did. We'd roam all over town, the campus, and even corn fields on our bikes, and our parents had no idea where we were. What I can't remember is how we always managed to get home in time for dinner. In the summer, we'd go out again after that and were supposed to be in by dark, but we never were. There was always the insistence, "It wasn't dark yet!" — and when we got watches, we'd set them back so we could come in later. As if that would fool our parents. ;-) Nothing bad ever happened; the worst thing was that we'd get bored and have to think of something to do. I often wonder if kids in Urbana still live at all this way. I mean, you can do a lot there without having to be driven places, and it's still a relatively small city.

I love this! It amazes me that my friends and I regularly spent whole days running around outside unsupervised as 4-year olds, but we did. (My parents didn't worry because we had a Lab who would nudge me off the road when I wandered into it! No sidewalks where we lived.) My kids spent the first half of their childhood living on a creek in a small mountain community, having experiences much like those of your kids. They are similarly independent and adventurous now. I feel so fortunate that we were able to give them the childhood they had.