As far as I know, the earliest years of my childhood were pretty great. Reasonable parents. Food on the table. No bodily injuries, except for needing to have my stomach pumped when I was two, after pouring a bottle of codeine-laced cough syrup into—or onto—myself. No one could be sure how much I ingested, so they erred on the side of caution.

Unfortunately, my memory sucks rocks. While some of the deficit, at this point, is surely a side effect of too many birthdays, it’s also just who I am. Other than what shows up in photographs, like the brown linoleum floor where we gathered for a Christmas morning photo when I was a baby, I can’t begin to picture the house I lived in until I was six years old.

Also, I should add, this was Kansas. Kansas! When winter was still winter! There we are on the cold, hard floor, my mom’s bare ankles hanging out. It’s a wonder we didn’t all die from exposure. But we didn’t, and I never lost any toes from being half frozen, so it must have all been okay, even though I don’t remember any of it.

My memories are visually driven. If I can’t see it, there’s a solid chance I’ll forget it. I can’t conjure up how it felt to be loved or tortured by my older siblings when I was small. Zilch on visits to Herr Doktor, outings with playmates, favorite toys. No recollection of snuggling into someone’s lap for story time.

Which brings me to a particular storybook.

I feel the need to tread carefully here. If your parents or grandparents were of a certain generation, or from a certain country, or you have recurrent, disturbing dreams about losing your thumbs, you may need to have some smelling salts handy before you proceed. Fair warning.

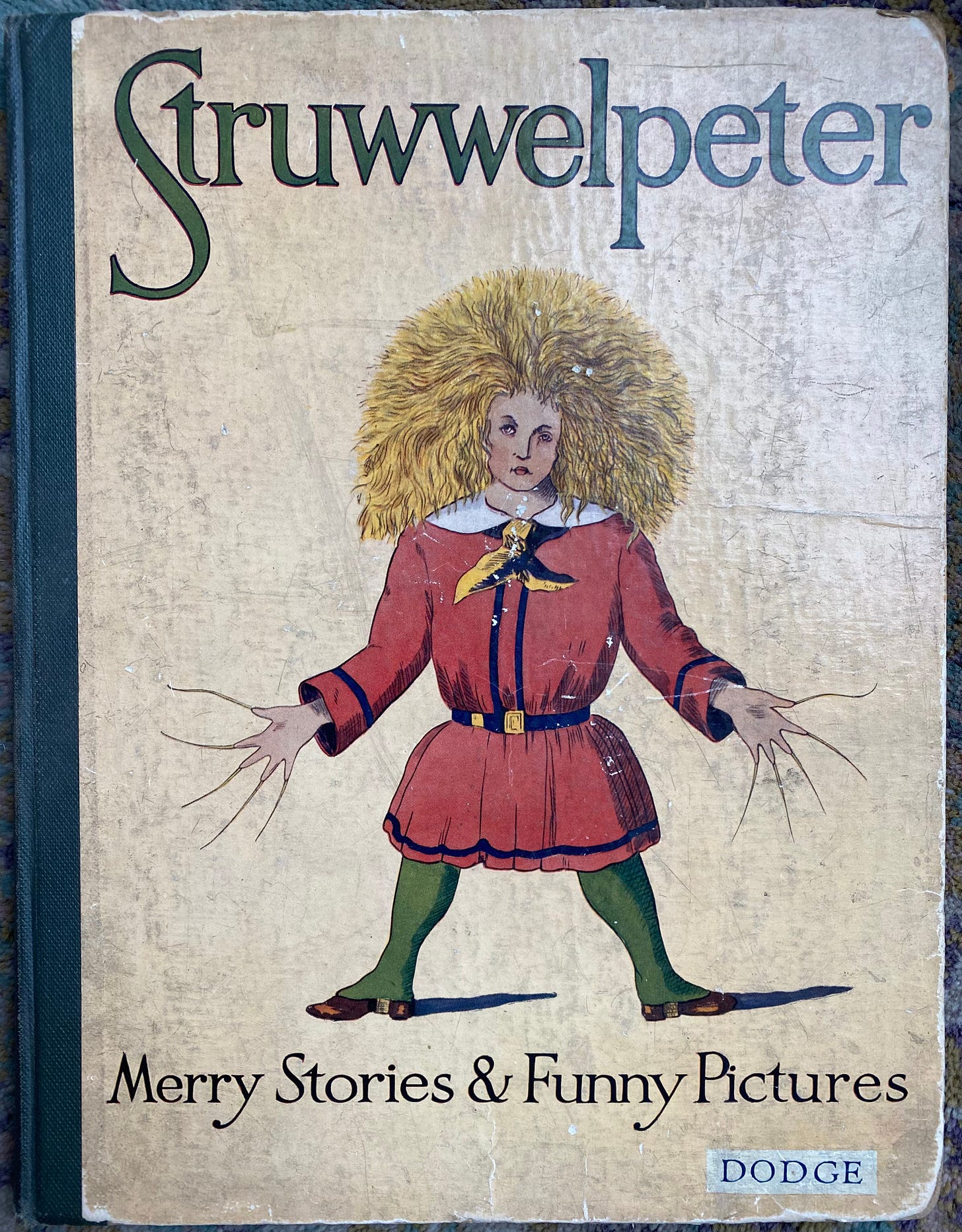

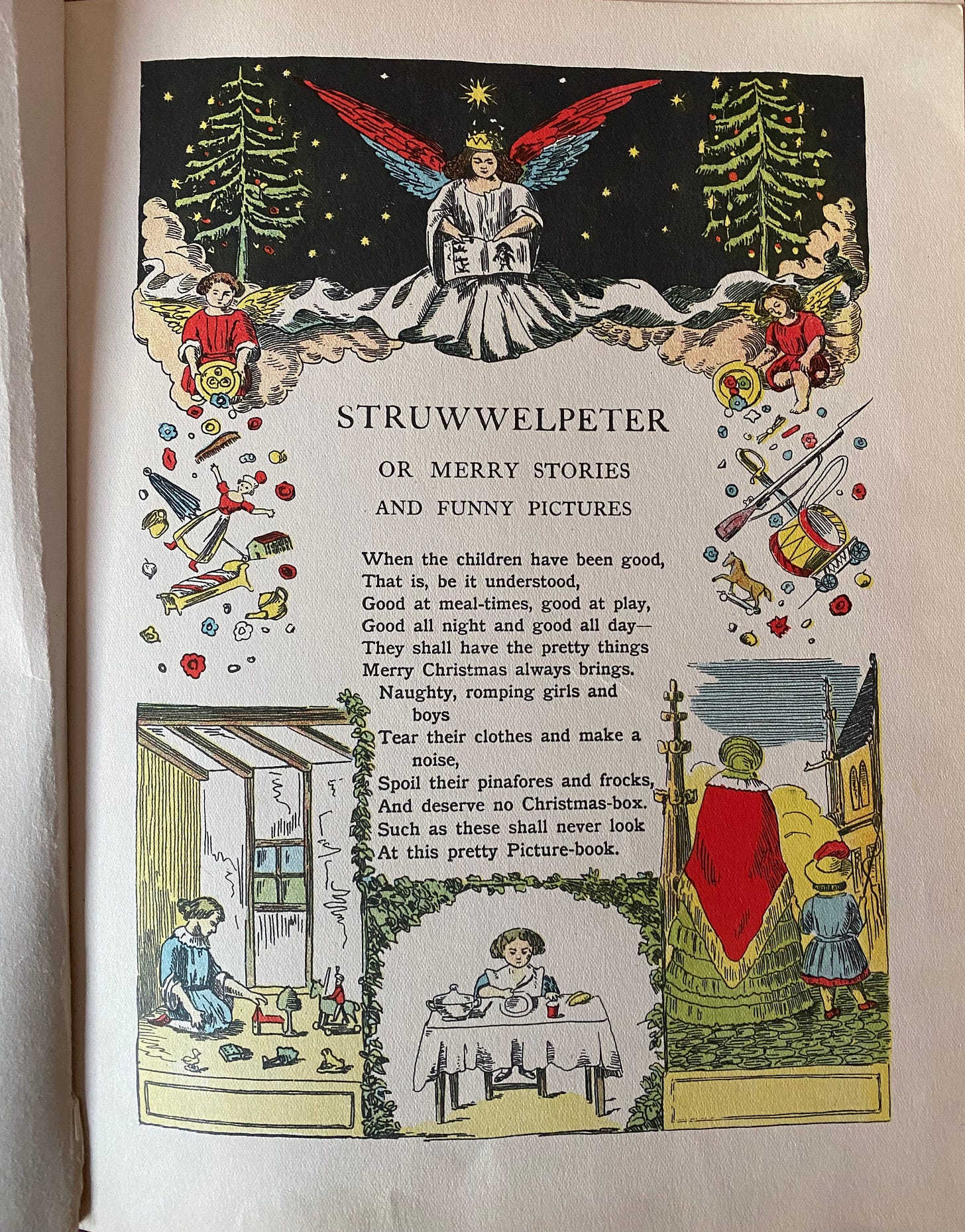

Struwwelpeter: Merry Stories & Funny Pictures

When it was first published, the book was called Lustige Geschichten und drollige Bilder mit 15 schon kolorirten Tafeln fur Kindervon 3–6 Jahren. For those, like me, who don’t know German, that’s Funny stories and droll pictures with 15 beautifully colored boards, for children ages 3–6. Sounds riveting, right?

Here’s the kicker: It was! Right from the start.

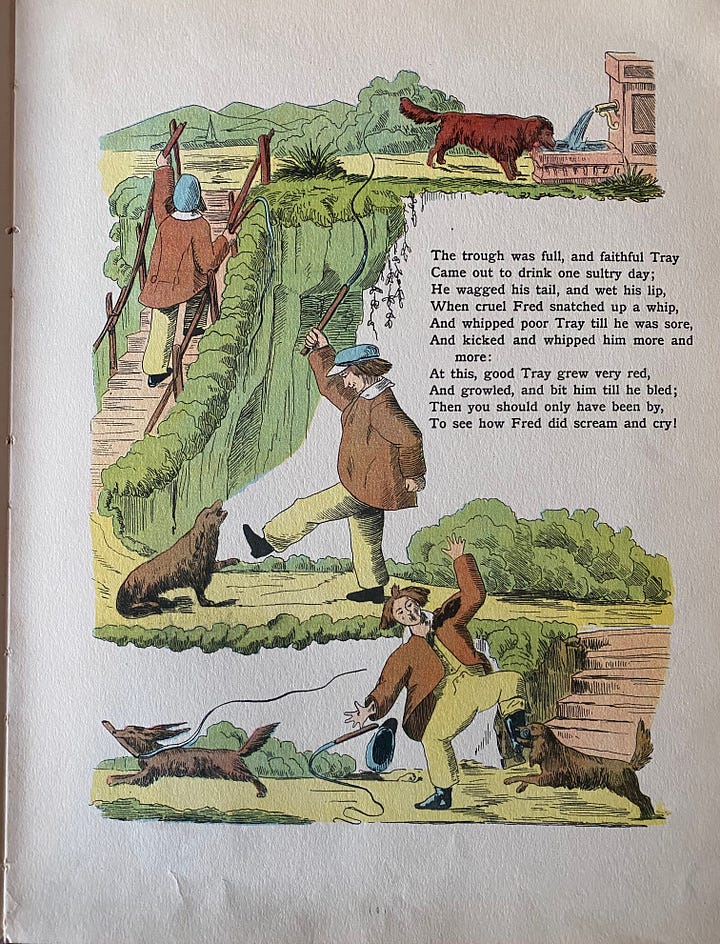

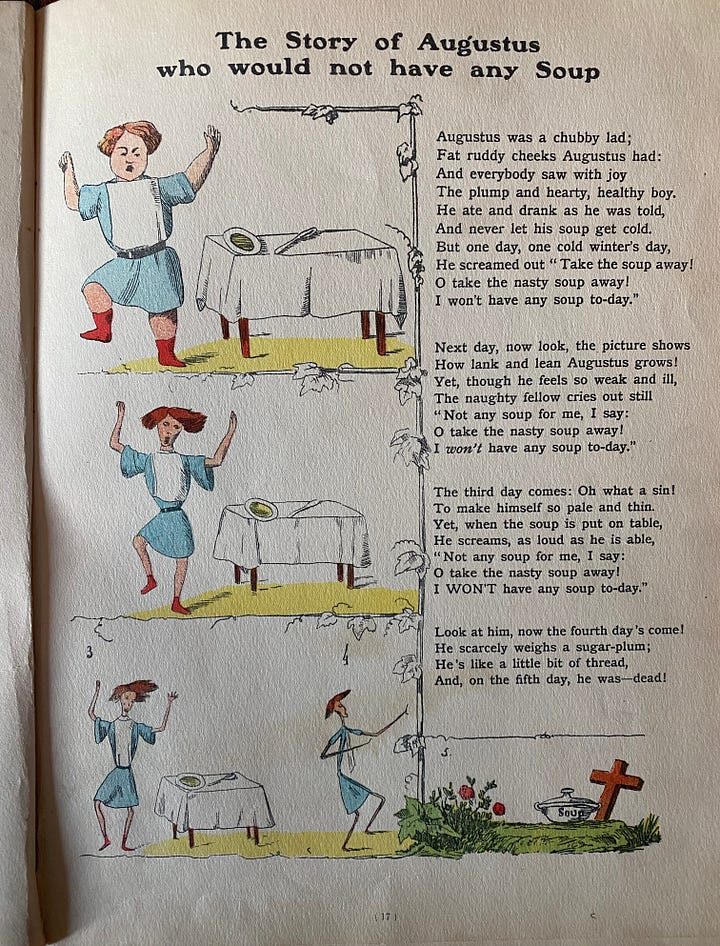

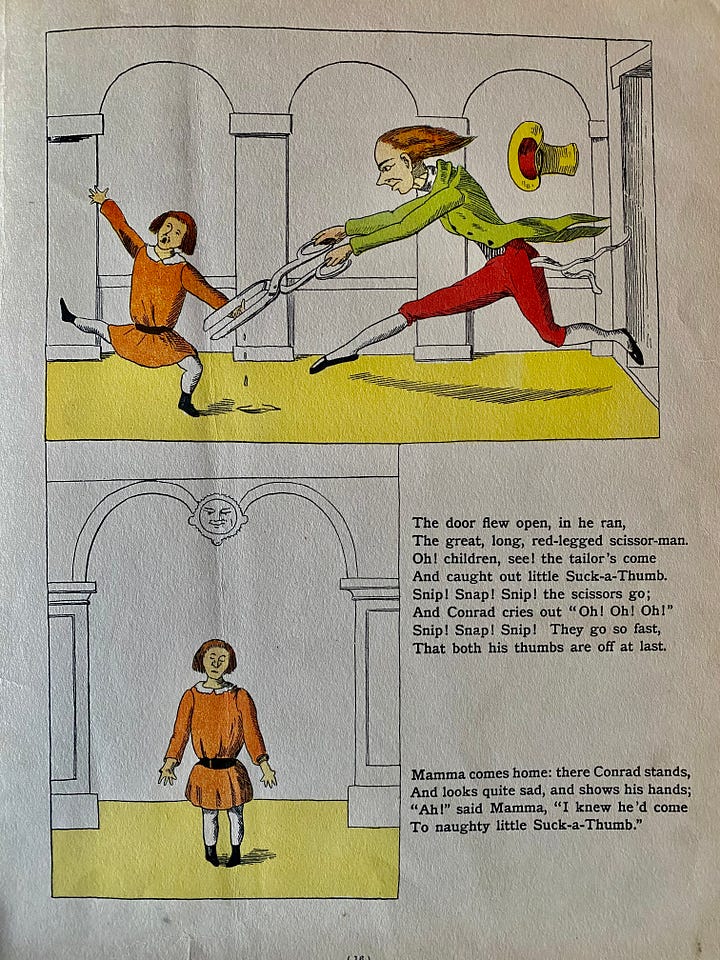

And here’s why: It’s not an ordinary children’s book. Not now, and not 180 years ago, when it was first created. It is a collection of horrid and brutal, yet also humorous, classic, rhyming, didactic tales of what happens to naughty, misbehaving children. Each story is likewise coupled with colorful, graphic illustrations of these same consequences. (Click the images here for a larger view.)

A child who plays with matches catches fire and is reduced to a pile of ash. A child who is cruel is bitten by the dog he mistreats. A child who rejects his soup starves to death in a matter of days. A child who sucks his thumbs has them cut off by a tailor with a giant pair of scissors. (I warned you!) A child, Struwwel-Peter, who refuses to groom himself is unloved.

That’s “Strew-ull-Peter” in English and something like “Shtroo-vul-peh-ter” in German. I need to practice my guttural r.

Now, we’ve already established how it’s possible that I have forgotten any fear I ever felt about this collection of stories. But, given that they followed me all the way into adulthood, and I have the text sitting right next to me, right now, you’d think I would pick up at least a little creep factor from its yellowed pages, if such a vibe existed. In fact, my reaction is the opposite.

I love this book! I love the way it smells. I love how the pages are printed on just one side. I love how utterly unorthodox it is.

The version of Struwwelpeter that lives in my library has no publication date, nor does the author’s name appear anywhere on the volume. Based on other antique children’s books I inherited from my family, I’m guessing this copy was printed in the 1930s.

The book originated in Frankfurt, a hand-drawn, one-off created by Dr. Heinrich Hoffmann. A father, kind-hearted physician, and well-regarded, even progressive, psychiatrist, the author was purportedly unable to find a book he liked for his three-year-old son’s Christmas gift. So, he created a collection of his own stories and drawings instead.

Shortly thereafter, on January 18, 1845, a group of Hoffman’s literary friends encouraged him to publish the work. Three years hence, 20,000 copies had been sold and the slender, 15-page book was in its sixth edition. Eventually, the title of the book was changed to that by which we now know it.

From humble beginnings, the quirky, moralizing Struwwelpeter became an unexpected and enduring success that influenced the future of children’s books worldwide.

As its popularity soared, new stories were added and illustrations were edited. Other authors took note. In 1891, Mark Twain translated it to English and called it Slovenly Peter, but due to copyright issues, his version was not published until 1935, twenty-five years after his death. The writings of Rudyard Kipling, Maurice Sendak and Roald Dahl were shaped by it. The book spawned parodies and plays including Shockheaded Peter: A Junk Opera by the Tiger Lillies. It was the inspiration for the lead character in the 1990 film, Edward Scissorhands. It appeared in a 2006 episode of The Office and in the 2015 film A Woman in Gold. It has been translated into more than 35 languages.

The book is included in countless scholarly discussions of children and childhood, with topics ranging from authority and power, to racism, to mental illness, to violence, to death. Calling it controversial is an understatement.

Today, you’d be hard pressed to find a copy in the children’s section of any library, and it has been removed altogether from libraries around the world, including many in Germany. But that doesn’t mean it has fallen entirely out of favor.

How can something so disturbing, so antithetic to what we think of as appropriate for children be so simultaneously captivating and appealing?

This: Hoffmann’s stories are an exaggeration. They’re meant to be a funny, if twisted, way of teaching children to do as they’re told, a book of cautionary tales so outlandish that reality itself becomes, somehow, less burdensome.

It’s worth remembering that, once upon a time, classic fairy tales like Sleeping Beauty, Red Riding Hood, and Pinocchio were much darker stories than those we now tell. Themes of revenge, abuse, disfigurement, and death were common. Case in point: in their attempts to fit into Cinderella’s slippers, the original evil stepsisters mutilated their own feet.

Look ma! No toes!

More, children from centuries past were not given the privilege of coddling we now offer to our progeny. They were pushed toward responsibility and punished into obedience. As suggested in the opening lines of Struwwelpeter, were a child fortunate enough to be given such a bright, beautiful book, surely that put them beyond the reach of the comeuppances that befell the children described therein.

With those considerations in mind, it becomes more plausible that the poetic lessons and perky illustrations in Struwwelpeter were viewed not only as benign, but also potentially hilarious. When Hoffman went out in search of something for his little son, the children’s books he found were likely lacking in color, imagination, and delight. I believe he believed his stories were an antidote.

To me, a modern reader, there’s something about the brevity. Or, maybe it’s the lyricism paired with the bright illustrations. Could be I’m just not quite right in the head. Would I give it to a three-year-old? Well, no. I’m not that far gone. Yet. Would I, like my parents, keep a copy around to show an age-appropriate grandchild, as a way of remembering the past, as a reminder of how far we’ve come, and a conversation starter for how far we have left to go? Absolutely!

I have another theory about why a comically drawn, unkempt boy and his wayward friends might have had such lasting appeal among children, despite their terrible stories. It relates to the notion of erring on the side of caution. But that, friends, is a tale for next time.

~Elizabeth

p.s. I’m assuming you’re not as inclined as I was to tap into your inner, vintage book nerd. If I’m mistaken, feel free to seek out the following resources which were used in the creation of this piece.

“A Classic Is Born: The "Childhood of Struwwelpeter,” a 2003, 248-page scholarly article by Walter Sauer and published in The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America

“The Influence of Struwwelpeter,” a 2013 essay by Jack Sherefkin, in the New York Public Library online archives.

Sarah Laskow’s 2017 article in Atlas Obscura: “The 19th-Century Book of Horrors That Scared German Kids Into Behaving”

A 2019 piece from Rae Alexandra for KQED: “How One Brutal Children's Book From 1845 Left Permanent Marks on Pop Culture”

I too have an old battered copy of "The Golden Story Book" full of beautiful Arthur Rackham-style drawings that I loved BUT it also included a few of the (very terrifying to me) Heinrich Hoffmann poems. I found this post especially intriguing because I wrote about poor Augustus and that awful Scissor Man on my own blog a number of years ago. I do believe that the British illustrations of the Scissor Man are much more sinister! Have a looksee if you like and love your substack! https://www.speranzanow.com/?p=402

Loved your piece, Elizabeth! All very familiar to my childhood, in the fifties, in Brazil. Adorable and scary, and very much life like!