It was good fun. Friends who, before the pandemic, made weekly opportunities to come together to walk, were finally reunited on the last day of the year. We took our usual 3-ish mile route, dipped in and out of conversation as the shape and pace of the group shifted, then returned to my house for a potluck brunch.

All the foods you might imagine showing up at such an event were represented: syrupy delights, little sandwiches, veggies and fruits, cheesy things and cakey things. Oh, and mimosas. That’s a given, right?

An unexpected offering came from a friend—a vegan, Jewish friend—who brought a green salad. Colorful and flavorful, it wasn’t the salad, per se, that captured my attention. It was one of its ingredients: black-eyed peas. Until I mentioned it, she’d never heard of eating them for New Year’s to bring luck and prosperity. In fact, no one in the group seemed to know of the custom.

The fortuitous, fresh salad was delicious and disappeared in a jiffy, but I still had my own traditions to uphold. My New Year’s food ritual is Hoppin’ John, which I’ll get back to in a bit.

Despite three years on Long Island when I was newly wed, I’ve spent the last 30 in Maryland and developed what cooking confidence I have here. Though the state is below the Mason-Dixon line and has its share of people whose behavior leans that direction, who bless my heart, call me hon’, and who might take exception to this assessment, it generally acts more Northern. My mother, who made all the meals in my childhood home, save for grilled slabs of meat, was a New Jerseyan who raised her family in North Carolina, via Hawaii and Kansas. Her mother was from Iowa. My matriarchal culinary roots are literally all over the map. But my father was a true Southerner, as were his parents before him. So if I’m going to wax poetic about food, there’s a good chance it’ll be grounded in that ancestry.

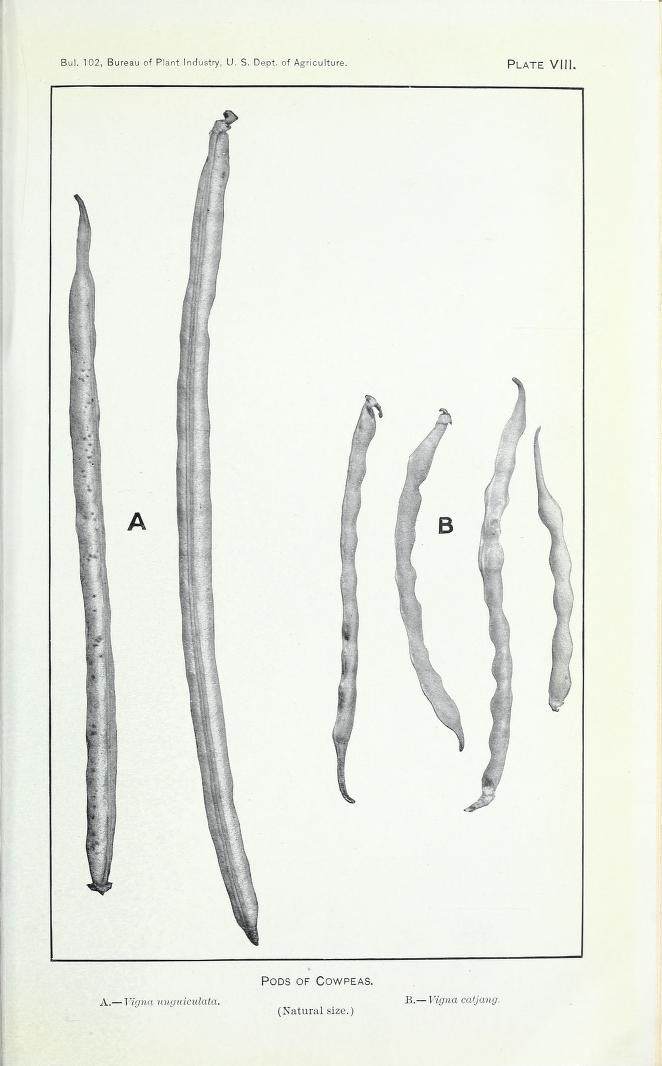

Enter okra. Enter corn pudding. Enter cowpeas, also called Southern peas, Indian peas, African peas and, commonly, field peas. Even if you missed learning about the good luck tradition, you surely already know about black-eyed peas. And you might have run across crowder peas somewhere along the way, so named because of how they are crowded together in the shell. But these earthy, little orbs are so much more.

First, though it mostly seems inconsequential, they’re technically beans, not peas. They can be solid, speckled, or marbled. They come with and without “eyes.” There are spotless cream-types, and there are purple hulls which have (you guessed it) purple pods. Endearing names like Big Red Ripper, Green Dixie, Hercules, Hog Brain, Whippoorwill, Knucklehull, and Zipper Cream sound to me like nicknamed farmers congregating in the shade of a front porch while they go on about when it last rained.

In the early 20th century, the origins of the plant were linked to Afghanistan and India, but subsequent research, with the aid of DNA testing, proved otherwise. Cowpeas started in Africa, and now they exist everywhere except Antarctica

“Utilizing archeological, textual, and genetic resources, the spread of cultivated cowpea has been reconstructed. [It] was domesticated in Africa, likely in both West and East Africa, before 2500 BCE and by 400 BCE was long established in all the modern major production regions of the Old World, including sub-Saharan Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, India, and Southeast Asia. Further spread occurred as part of the Columbian Exchange, which brought African germplasm to the Caribbean, the southeastern United States, and South America and Mediterranean germplasm to Cuba, the southwestern United States, and Northwest Mexico.”

I’m fascinated by the way foods find their way to us and bring their stories with them, the most ordinary often carrying the most significance.

According to some, there was a time in North America when cowpeas were considered little more than livestock food. From there, it’s not hard to imagine how they might have become a food for the enslaved, who were treated like chattel.

There are accounts of cowpeas being key to survival during the Middle Passage, the horrific, seagoing leg of the triangular Atlantic slave trade, in which African men and women were forced to sail, en masse, to Caribbean and American shores, where they were sold into slavery.

There are legends that center the luck of black-eyed peas in the winter survival of beleaguered Confederate soldiers, explaining how Sherman’s Civil War troops, who pillaged and stole everything else, felt the beans were unfit for them to eat and so, left them behind.

True to the heroism and determination required of enslaved people, there are countless stories of grains of rice, and seeds like field peas, being woven into the braids of enslaved women, both before their grueling ocean voyage and, later, as they escaped to freedom.

Inspiring though they may be, these narratives lack validation, leading some experts, including Patricia Turner, professor of African American studies at University of California Los Angeles, and writer and culinary historian, Michael Twitty, to suggest that they are the by-product of oral history and imagination.

Yet both scholars are also careful to note that it is not the stories themselves but the resourcefulness and resilience they represent that is most important.

My Southern heritage imbues these aspects of the cowpea’s past with feelings of deep connection and sorrow, but I would be remiss in not also mentioning that there are practices that date back much farther than early America.

As one would expect, cowpeas were popular in Africa long before the nasty Europeans arrived, and they were symbolic. Often included in meals prepared for births, deaths, and homecomings, they were thought to bring good fortune and to ward off evil. Forced from their homeland, enslaved Africans brought along their customs. From stores of cowpea seeds traveling with them, it’s said they grew out plants on plantations and, over time, influenced the adoption of the beans into the white American diet.

One of the oldest traceable links to the cultural importance of the cowpea goes back to Babylonia (now Iraq) and the Jewish Talmud, where it is written:

“Now that you have said that an omen is significant, at the beginning of each year, each person should accustom himself to eat gourds, black-eyed peas, fenugreek….”

In The Jewish Connection to a New Year’s Soul Food Classic, a blog post by Joel Haber, we learn more:

“The earliest Jews to move to America, particularly in the South, were those of Sephardic descent. Having spent much time in North Africa and nearby Spain, they recognized black-eyed peas as the nutritious and tasty ingredient they are, and thus happily ate them in America as well… [W]hile we have no way of knowing with certainty, one of the most plausible reasons for the Hoppin’ John/New Years [sic] connection is that Southern African-Americans saw Sephardic Jewish-Americans eating their black-eyed peas specifically on their New Years [sic], and adopted the custom for themselves.”

Conceivable? Ridiculous? Like many stories from the past, we’ll probably never be sure. It’s human nature to want to link our experiences to people and places in history as a way of defining who we are, and who we aren’t. But cultures merge. Traditions mingle. The Hoppin’ John I’ve braided into my celebrations at the first of the year is an amalgam of my childhood, my kin and theirs, the hideous and resilient legacies of the South, and my love of good food.

The cowpea: a humble legume—a plant that tolerates intense heat and poor soils, adding nutrients to the ground in which grows, a plant whose leaves, pods, and seeds are edible—has sustained the hungry, galvanized the oppressed, and stirred hope in those of us looking for the assurance of plenitude wherever we can find it.

This New Year’s Day, I felt tired. As wonderful as they were, gatherings with friends throughout the holiday season required more social energy than I’d been able to regenerate. And the news. Always the news. I should know better than to turn my attention there when I’m already a little depleted. But upholding tradition matters to me.

I unearthed a quart of black-eyed peas from the freezer. The date on the label read January 7, 2023. I had every certainty that the savory cooking liquid I’d frozen with them a year ago would have preserved them perfectly, and anyway, it was just me and the mister. No need to fuss over good impressions. He loves me and my cooking.

I tossed a glob of bacon grease into my 12” cast iron skillet and turned the heat to high, adding in a chopped onion, a couple cloves of garlic, and a minced jalapeño. I cut up the last of my garden tomatoes, the ones I’d picked just before the first real freeze came through. When was that? I can’t recall now. Seems like an age, but they were still surprisingly tasty. I sprinkled in some seasonings—rosemary, thyme, a dash of cumin, salt—and pushed it all around with wooden spoon for a few minutes before pouring in the black-eyed peas with their liquid. The smell, while it simmered, boosted my spirits. Minutes before serving, I added some cooked rice and a splash of hot sauce.

It wasn’t the best Hoppin’ John I’ve ever made, but it was warm, and filling, and reminded me of home.

~Elizabeth

That's awesome! There's such a diversity of legumes available. I aspire to use them more often but having not grown up with them I'm usually uncertain how best to use them. Thank you for sharing!

Yes to Hoppin' John on New Year's and for me always served with corn bread drenched in butter and honey!

Your recounting of the many names of beans made me chuckle and reminded me of the nicknames of the older water men of The Eastern Shore!

Here's to more walks, more food, and a loving and supportive tribe!