Do you remember where you were, or what you were doing? The people around you or the color of the room, the smells, the sounds, the silence?

I was at the kitchen counter in the midst of an ordinary morning, animals tended, kids fed and occupied with something-or-other*, when the phone rang. It was a friend and fellow farmer, not someone who called frequently. She asked if I knew what was happening and advised me to turn on the television.

The north tower of the World Trade Center had already been struck. I watched in fear and disbelief as the second tower appeared to explode. Images and words spewed out of the screen into my bucolic existence as I tried to offer my daughters a form of explanation about what was happening. I wasn’t sure myself. I called my spouse. I worried about our safety, living as we do in relative proximity to the nation’s capital, about his family, who live in New York, and friends who live in Washington, D.C.

Sometime later, I ended up at the home of a neighbor whose children are a bit older than mine. We spent the rest of the day together, the kids keeping each other entertained, while the two of us consoled each other and tried, fruitlessly, to process the magnitude of it all.

That night, my nuclear family tucked safely under our own small roof, I took note of what was missing. Living below the flight paths of several major airports was never more noticeable. The farm, at the end of a dirt lane on a lovely peninsula, was sheltered from street noise. But, the constant drone and blink of airplanes overhead never fully registered until, suddenly, they disappeared.

These are stories I tell myself about what took place 22 years ago, on September 11, 2001.

Some details, I remember vividly. I’m sure it was Ruth who called that morning. I spent longer than I should have glued to the television before leaving for Debie’s house in search of companionship. Was the footage I watched that morning live or replayed? Did I arrive after her children had been sent home from school, or before? I have no idea. I’m not certain I called my husband or if, instead, he called me. I have no recollection of getting in touch with his family, but instinct tells me that we did. It’s possible we noticed the eerie silence of the airways that night. It’s also possible that we fell into bed, exhausted, and only noted the absence of plane activity the next day.

A commanding, muggy breeze brought slaps of brackish water onto the shoreline in a hectic rhythm, like 1940s tap dancers. It was a sound we’d heard countless times before, soothing in its own way. We went to bed around 11 o’clock, shortly after walking the full perimeter of the property. Uncharacteristically, I slept straight through to sunrise. When I got up to look out the east-facing windows, I was shocked to discover that our cottage was completely surrounded by water, the bases of nearby trees submerged, the chickens and their mobile coop stranded on a small, new island about 100 feet from the house.

I awakened my husband in a panic, sure that we needed to start moving our belongings to the loft, to save them from ruin. It was he who discerned, from the dark lines on the trees, that the water had already begun receding. The highest point of the storm surge had crept in overnight. We lost most of our crops to the flood but were otherwise unscathed. Despite it all, we never lost power that day.

Twenty years ago, on September 19, an excessively high tide and storm surge from Hurricane Isabel took my little part of the world by surprise.

The truth is, I have no idea what time I went to bed the night before the surge. I’m not even sure I remember the sound of the waters dancing against the shore or if I etched them into my memory later. I know there was a warm, stiff breeze and that I slept well, thinking all the hurricane hype was overblown. While it’s true that our cottage was enveloped by water the next morning, pictures taken show large swaths of exposed grassy lawn. My mind’s eye sees it otherwise. It did not occur to me until much later that we should never have stepped into the flood waters around our house without first shutting off the power supplies. We were fortunate in so many ways.

As my mother and I prepared to catch a flight home from Ireland, I saw the announcement of Michael Jackson’s death on a big screen in the Shannon airport. The walls around me were green. The monitor was on my left as I walked past, and the newscaster was a woman. The iconic pop star was not so different in age from me, his music integral to my youth, his death completely unexpected. I don’t think the news made any real impact on my mom, but I had to choke back tears.

It was Thursday, June 25, 2009.

I’ve held this story, and its details, in my mental repository for years. It’s not one I have occasion to retell very often. Without the benefit of Google, I might have remembered the year, but not the fateful date. I’m sure we were in an airport in Ireland, but it is the trip itinerary, not my memory, that places me in Shannon. I can’t even be sure of my tears. I know of no living witnesses to affirm or refute any part of this story.

All of these accounts are what scientists call flashbulb memories, vivid, long-lasting recollections of surprising or shocking events that happened in the past. Like scenes illuminated by camera flash and captured in a photograph, memories like this were long thought to be both detailed and accurate. But, studies show otherwise.

It turns out that the particulars we recall about such incidents grow less reliable over time—25% of study participants who shared memories about the Challenger space shuttle explosion provided different details of their stories a few years later.

Flashbulb memories are associated with events of personal consequence that also include elements of surprise and heightened emotion. Generally, they are as likely to fade or change over time as other kinds of memories. What sets them apart is our belief that they are correct, even years later. With flashbulb experiences, our confidence in the accuracy of our stories remains firm.

It was research for this writing that caused me to reconsider the memories above, and still, I only doubt the veracity of certain parts of the stories. If it were possible to replay the actual run of events for any of those occasions, I might find discrepancies even with what I currently believe to be true.

If you’re feeling like I’ve opened a substantial can of worms here, you’re right. Brain function, and the way we store and recount memories, is a topic too big for this platform, or at least for me. The science continues to evolve. I find myself reflecting on the fallibility of my own longstanding stories and others’. What about the eye witnesses who are so critical to many of our court cases? What about stories of historical significance that were built on visual accounts? If memories are just the stories we tell about our experiences, what prevents us from revising the painful ones in ways that could help us heal?

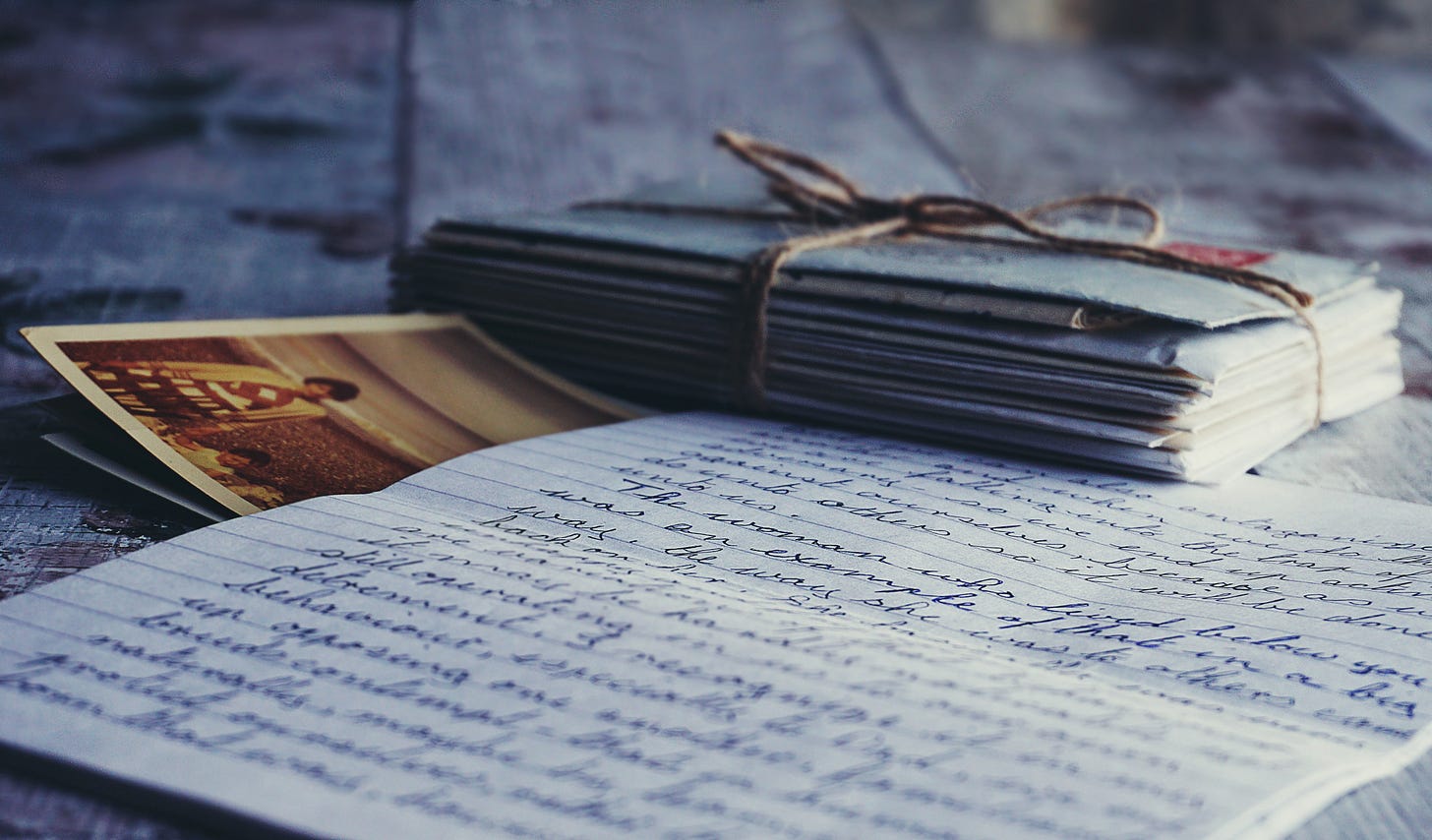

Last weekend, with my husband’s help, I finally put away a collection of boxes that have been taking up space in one of our bedrooms for more than two years. Many contained letters saved across a lifetime of correspondence to and from my mom. I look forward to going through them someday, perhaps this winter when more of my gardening and farm-related work will be on hold for the season. I am especially interested to read what I wrote to her. I fell out of the habit of journaling for many years, but I maintained my letter-writing. The words on those pages represent my best hope for rediscovering what I once believed I would never forget.

~Elizabeth

*P.S. I’m taking advantage of the digital nature of these essays to do something I’ve never done before: I am making a real time edit. Subscribers who read via email might miss this nugget, but it’s so germane that I am compelled to include it right away. A few minutes after publishing, one of my kids reached out to share her memory of 9/11, saying, “I have always thought and had memories of being at preschool when [that] happened .” She offered a few other comments about her recollections from the day, one of which, we agreed, couldn’t be right. But, her notion of being at school is, without a doubt, spot on! Her big sister would have been in first grade elsewhere. So, my version of the story, the one that has them with me as the news broke, I now believe is completely fabricated. I imagine I wove them into my tale because I so desperately wanted them with me. Gosh. How remarkable.

"The words on those pages represent my best hope for rediscovering what I once believed I would never forget." Sigh. What an exquisite observation and powerful reminder.

I discovered the fallibility of my memory when I read an event in my journal that I remembered differently. After that I have been more diligent about writing down the things that happen in my life and want to remember within a day, because I discovered how faulty and deceptive my memory truly is.