My 7th grade history teacher was a gangly man who also coached basketball. He wore his thinning hair in a comb over that sometimes lost its overness as he sprinted down court. That was exciting. I didn’t much care for his lessons, though, and by association, him. All those wars, all those godforsaken ages and eras – why did they matter? Possibly it was the way he taught it, or probably it was the way I heard it, but the connection to individual lives was lost on me. Lacking the ability to anchor any of it to my own experience, everything drifted around in, and mostly out of, my head. I spent more time analyzing the mechanics of my teacher’s hairstyle than I did the workings of the country.

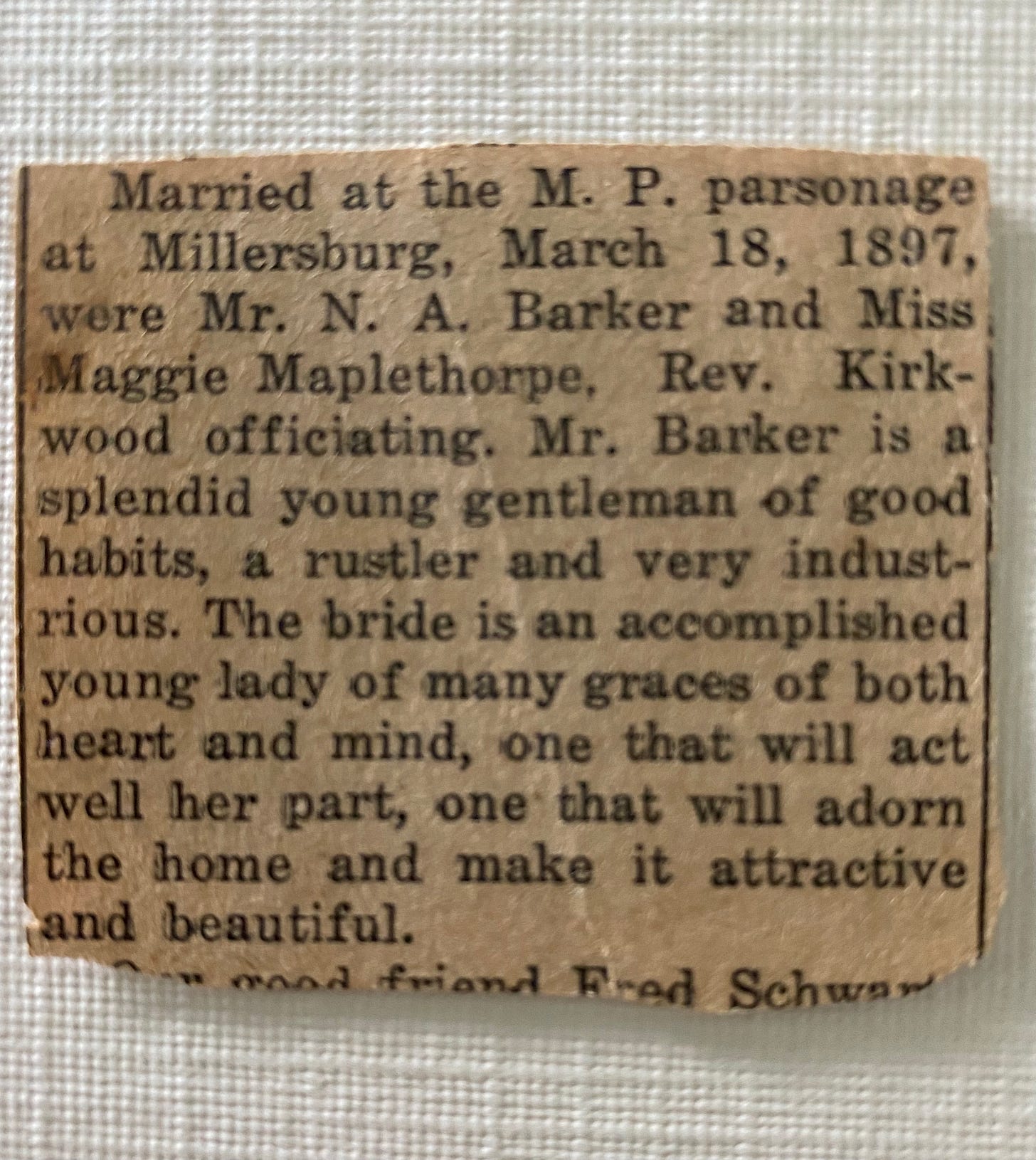

The yellowed, 2”x2” clipping dropped from its spot between the old photographs and landed on the bed. No bold headline, no photo, nothing particularly remarkable about it. But, its news had just turned 125 years old, and between the lines I caught sight of a marvelous story.

Nathan Alson Barker was killed in an automobile accident in 1939. He was 71 years old. He had been married 41 years. By the time I was in 7th grade, he was long gone. It didn’t occur to me to want to know more, until now. I did not expect my great grandparents’ lives to have much relevance to me, in 2022. I was wrong. And that, friends, is the moral of the story I am about to tell.

Born in 1868, Nathan Alson Barker was my maternal great-grandfather. At 24, he moved to Iowa from his birthplace in Tennessee. I presume he made his way there by train. The Transcontinental Railroad, completed a year after he was born, would have been a reasonable way to travel at that point in American history. Nonetheless, some of the vintage family snapshots show unnamed people standing next to covered wagons, so I can’t be certain he didn’t get there under bona fide horse power. He was an energetic man, after all – a rustler, according to whoever wrote the wedding announcement. Given that my kin are a storytelling bunch, I’m fairly confident his industriousness was not applied to stealing livestock. I’d surely have heard that tale told a time or twenty.

Nathan married Maggie when she was 21. I don’t know how he met her nor anything about their courtship. I have no knowledge of whether they lived in the same town or met elsewhere. I wonder if they had much in common or if he, pushing 30, just needed to find someone with a good foundation. They must have hammered out a thing or two, because they created six children, five boys and lovely Lola, the lone girl sandwiched between all that testosterone. My grandfather, the oldest, was named Virgil Dewey. They called him V.D. for short. Vee-Dee. Jiminy Christmas, Nathan, what were you and Maggie thinking?!

Available records offer no insights into what Nathan did to support his family, and anyone who might have been paying attention to the erstwhile anecdotes is now on the wrong side of the grass. Still, I can stitch together a feasible scenario for his bride. Like scores of women before and since, Maggie spent an epoch pregnant, nursing, diapering, burping, rocking, bathing and nurturing her offspring. Alongside the unremitting responsibility of keeping children alive, I picture this woman in an elbows-deep cycle of canning, plucking, cooking, sewing, washing and mending both people and things. There would have been endless house cleaning. There may have been quilting bees to attend, and church - definitely church. There was the expectation that she should be interested in her husband’s business affairs. All this, borrowing from the wedding announcement, to act well her part, to adorn the home and make it attractive and beautiful.

Notice what the newswriter did there. He left it open to interpretation whether the House Beautiful obligation was to be fulfilled by Maggie herself or by something extrinsic. Here’s hoping she was savvy enough to work that matrimonial loophole to her advantage. Maybe she rubbed a mean washboard or beat a rug like nobody’s business. Because, seriously, any woman tasked with upkeep of a brood that size, particularly a gal without access to DoorDash or the occasional mani-pedi, gets props for even being functional, let alone attractive.

Ah, Maggie. Bless your heart.

I could go on with the yarn spinning, but you get the idea. In the early 1900s, life in Williamsburg, Iowa was no cake walk. Not for Maggie. Not for anyone, really, especially those who weren’t in charge. Here’s an uber-condensed review of the domestic and global landscape during the first ten years of Mr. and Mrs. N.A. Barker’s union.

There were 15 or so major conflicts taking place around the world. The French were conquering parts of Africa. The Japanese, Chinese and Koreans were duking it out. Ethiopia successfully shut out Italy, the Ottomans pummeled the Greeks. This is sounding like a sports commentary. But wait, the game’s not over!

The U.S. wrested from Spain ownership of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines, took temporary control of Cuba, and then, getting off on its winning streak, refused to acknowledge the proud, independent First Philippine Republic, resulting in a continued, brutal, five-year clash.

This to say nothing of the bloodshed taking place on home soils, most of it spilling from the battered bodies of Indigenous peoples who weren’t keen on giving up their native homelands to greedy white folks.

Middle class people were uneasy. Sure, the Second Industrial Revolution meant some aspects of their lives were improving – and, we’re not just talking about access to highfalutin gizmos like typewriters and automobiles, but also safety razors, crayons, and playing cards. Before 1910, three states and four territories had approved women’s suffrage. Votes for Women! But, industrialization had a way of scattering families, of increasing the gap between the haves and have nots, and of luring in scads of non-English-speaking people who were eager to get a piece of the action. Of course, all of this was taking place against the backdrop of political corruption. Something had to be done!

Between 1905 and 1906 Philosopher George Santayana wrote The Life of Reason: The Phases of Human Progress, a five-volume collection described by him as “a presumptive biography of the human intellect.” His oft-quoted text appears in the first volume: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

I’m not intellectually equipped to do much more than take that statement at face value, but anecdotally, it seems true. We certainly haven’t shown ourselves to be very capable of applying to today the lessons of yesterday, at least not in ways that keep us from stepping in subsequent stinky piles, often just after we finish cleaning our shoes. I would also offer, as a way of rooting out something other than eternal condemnation from our human inadequacies, that we may not be wired to do so.

History is boundless. It is the echo of accounts reverberating across generations, a never-ending conversation in which people engage and disengage, latecomers hearing only the essence of what mattered to the ones who uttered the first words. How likely are we to internalize the lessons if we can’t see ourselves in them?

In the Story of Now, the world feels no less precarious than it must have felt 125 years ago. At the bidding of authoritarian leaders, so many countries are ravaged by war. And yet, somehow, in countries where leaders are elected, these people continue to rise to power. Certain individuals, perching themselves on perceived intellectual, economic or moral high ground, remain on the offensive against anyone and anything that threatens their highness, often resorting to corruption to retain their positions. Technological advances improve our societies and, simultaneously, degrade our planet. Automobiles claim lives at a more aggressive rate than wars.

We assume we’d be better off if we could stop making the same stupid mistakes, but is it possible that resilience resides, at least in part, in letting go of the past? How do we make progress with fear of failure as our constant companion? How do we plant the next crop when we can’t be sure we will live to harvest it? Like the pain of childbirth receding when the next soul is ready to come into the world, or the heartbreak of loss giving way to a willingness to love again, perhaps our persistence as a species depends on an intractable belief that our stories will have different - dare we hope, better - outcomes.

Nathan, I’m going to feed the chickens. Look after the children while I’m out.

~Elizabeth

Betsy, What a lovely story about your family! And fascinating account of that era. Love how you articulate what we're feeling about history repeating itself. Handsome family photo. Bother upper right looks like your mom and Don.

Um, the memories of Mr. Stewart... not sure it was the teaching that made him less than appealing, as you diplomatically put it. Love this tale, and those pics.