Were he still alive, my father would be 100 years old today. A century is a meaningful milestone, but the reality is we reach a point when no one much cares about ordinary folks who’ve lived ordinary lives. In effect, that makes this a unique opportunity to acknowledge the humble contributions he made to his life, to mine, and to everyday people everywhere.

In places where he invested his energies, my dad was known for being civically-minded and successful, but on a grand scale, he was peanuts. Somewhere in the family archives—or maybe it didn’t survive the great purge—I recall a photo of him with Ronald Reagan. It was taken in 1976 when the former actor was aiming for the Republican presidential nomination and my father was president of the local Rotary Club. The hopeful candidate offered a talk, and my father had a brush of a brush with fame that has since been all but lost to time.

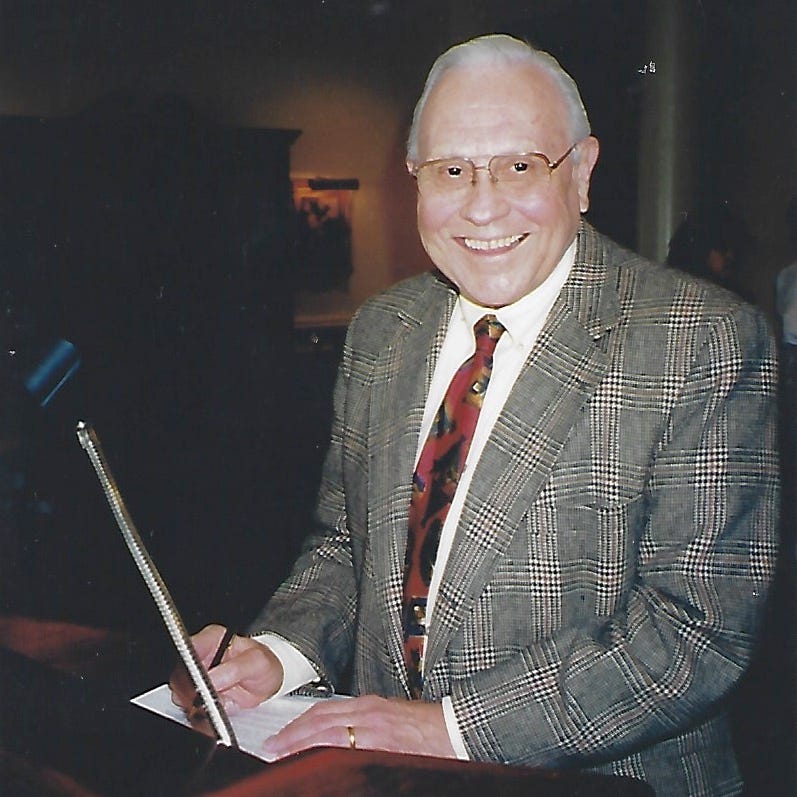

He was organized and affable, qualities that served him well as a military officer, salesman, business owner and leader. He could also be intimidating, prone to flares of temper, and to anxiety, traits he supposedly inherited from his mother.

Born in 1902, my grandmother was the archetypal southern woman, powerful in some ways, paralyzed in others. There were stories of her bouncing my adolescent father’s head against the floor in anger, as he lay pinned by the full weight of her body. There were times she retreated to bed for most of the day, on account of a “sick headache.”

She was married to a gentle, rural mail carrier and farmer, 17 years her senior, who died when dad was 42, and I was not quite five. They lived in Macon, North Carolina. The population in 1910 was 189, in 2020 it was 110.

Aside from all the ways well-attended children can thrive in a place with nothing to do but imagine, a highlight of visiting my dad’s sleepy hometown was watching the train clatter past once a day. It was a five minute walk up Oak Road to Main Street, and my grandad was always keen to go with us. I don’t remember much about him, but I remember how Nanny called from the porch as we left, telling him to be careful, mind the hand holding, and watch the children!

Her fussy tendencies followed my father to college, bless his heart, her letters often chiding him for not communicating frequently enough, though he sent mail at least twice a month. It’s no great surprise, then, that my dad came into adulthood with a complex emotional inheritance.

What’s astonishing is how infrequently anyone saw that side of him. He assumed the role of confident, convivial male, but if my intuition is correct, he second-guessed himself far more than he let on. In fact, I think it was fear that fueled most of his outbursts. When life fell into place, he was content and surefooted. When it startled him, or upset the certainty of his position in the world, he boiled over, then stewed about it afterwards.

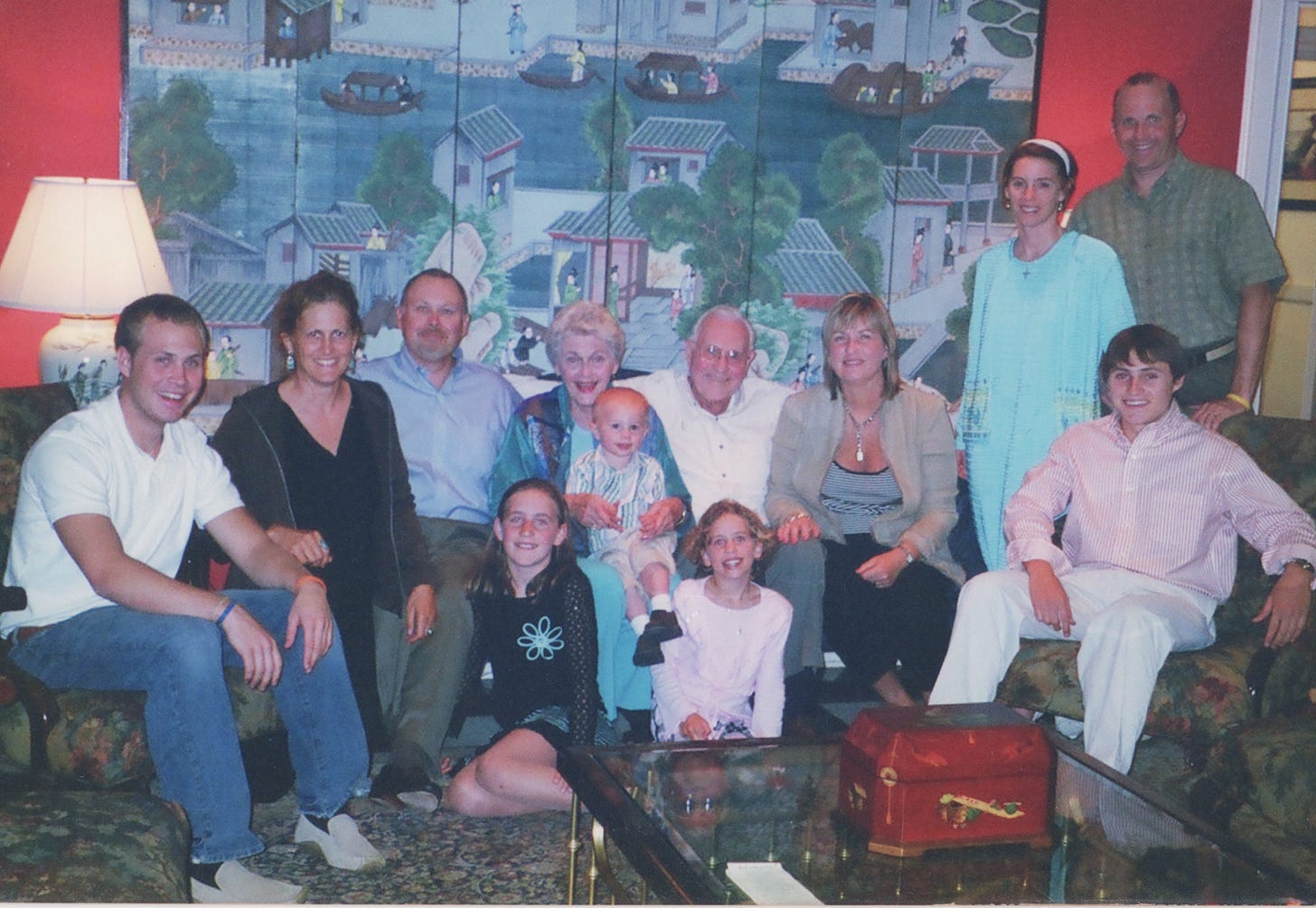

If a stereotypical family actually exists, mine was that. By no means perfect, it was certainly privileged and more functional than not. My father worked out of the home. My mother worked in it. She took primary responsibility for childcare, he for breadwinning. Still, when we were small, and he wasn’t on the road, dad changed diapers and soothed tears, he cooed and cuddled. As we kids grew older, he did what he could to remain engaged, to the extent he knew how to do that, and to the extent my mother invited him to try. As he grew older, his insecurities became more apparent, as did his more tender emotions. Perhaps both needed the expanse of a lifetime to come into their own.

My father was born on the heels of a pandemic. He lived through the start and end of the Great Depression, World War II, the Korean and Vietnam wars, the Civil Rights Movement and its associated horror of assassinations, Watergate, the Iranian hostage crisis and arms scandal, the Cold War, and 9/11. He was alive for the world’s first organ transplant, Neil Armstrong’s first steps on the moon, the razing of the Berlin Wall, the advent of color television, the Interstate Highway system, microwave ovens, computers and cell phones. He died just a few days after the election of America’s first Black president, one normal life bearing witness to so much.

I remember how dad’s voice, deep and resonant, emanated from his chest not his throat. I remember how he whistled two different ways, one a cheery, tuneful version, the other commanding and shrill. I remember how well he sang on his own and how he’d go wildly off pitch in a group. I remember how carefully he dressed for work, and for church, imposing those standards on his sons, who heeded them to varying degrees.

I remember how he preferred when I wore my hair short and how it irritated me when he nagged about me having hair in my eyes. Though I’ve had long hair for more than 40 years now, I can’t tolerate it in my face.

I remember how my father criticized my boyfriends, how he contemplated hiring a private investigator before I married my husband. And I recall a time in the middle of the night, after his cognitive issues were well established and his physical abilities were in sharp decline, when I offered some help with his personal needs. After getting him cleaned and back to bed, I remember how his eyes sparkled as he asked, “What do you know about boys?”

I think about how my father showed up for me and the rest of the family. He could be verbally harsh. For us kids, there were spankings and backhands. My mother said he raised a hand to her once and learned, that day, to never make the same mistake again. He worked with diligence and honesty, even when those around him didn’t. His integrity was unwavering. He told his wife how nice she looked on special days and on average days, when he could have said nothing at all. I don’t think any of us ever doubted his love.

Perhaps more than anything else, I remember how my father laughed. Everyone who knew him remembers how he laughed. Head back, face blooming, all the teeth a jaw can hold getting in on the act. The sound went from an open-mouthed bellow, to long, z-toned hisses, to whoops of hilarity, finally dissolving into fits of coughing, a carryover from his smoking days.

He laughed this way when he realized he’d been shaking the bottle of Tabasco sauce with the lid off, pepper-colored droplets flying all over the kitchen. He laughed this way when he and his buddies took in football games and hunting trips together. We heard it at almost every holiday meal, prompted by some well-worn anecdote. I hear it still, in my head, when those same stories circle back to me again.

My father lived a decent, devoted life. He, like most of us, did nothing especially out of the ordinary. He paid attention, he stepped in, he stood by.

My children knew my dad. My brothers’ children knew him. But any further additions to the family will experience only what we share of him. He’ll never have a Wikipedia page. He has no online footprint. There was no great material fortune left behind. He didn’t improve the lives of vast numbers of people. Musty pages and digitized records carry the vestiges of his time at the University of North Carolina and in the U.S. Navy. The waters of both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, and some of the lands in between, contain traces of the body he left behind. But the rest is down to storytelling.

This is what I want others to remember: My father was an ordinary man who made a difference anyway.

~Elizabeth

Do you know someone right here among us (Jimmy Carter is one) who will soon celebrate 100 years? Are there ordinary folks now gone who made a lasting impression on the person you are today? What do you wish you could ask them? What do you remember best?

Post likes, restacks, and shares help me reach other readers, which is really important to my work, but always appreciate learning more from you in the comments.

Also worth mentioning: I keep my work intentionally free so that people of all circumstances can have access. If it is within your means, please consider a paying subscription. You’ll be supporting this ongoing creative effort and affirming that you’re finding value in it.

Paid subscriptions to Chicken Scratch can be accessed here, and one-time contributions can be made here. Special thanks to Eileen for the recent Ko-Fi contribution! Any support is most appreciated.

I remember at some point realizing that, for most of us, once the people who know us all die, we will no longer exist in the way we do now--because most of us are ordinary in the way your dad was. You capture so beautifully why our lives matter anyway. Why they matter even though we are not perfect and do not always behave well. I so appreciate the way your portrait of your dad is both honest and loving; the honesty about his hard parts make the parts about your love for him more deep and true.

You ask about people we've known who are extraordinarily ordinary, and there have been so many it's hard to single any one out--family members, friends, teachers, colleagues, students would all be on my list. Your dad reminds me in many ways of my grandfathers, who were born in the 19teens. One, who died suddenly in 1981 when I was only 17, was a butcher. He fought in WWII, raised my mother and my grandmother's daughter from her first marriage, and cared for so many members of my extended family when they needed a place to stay. He golfed on Sundays, bowled on a team in a bowling league, and loved my grandmother easily and well. My family was boisterous, but he was quiet. While everyone else was laughing and telling stories in the kitchen, he was often in the living room, reading a book. He made me feel that I was probably biologically related to them all, which I sometimes wondered about. At his funeral, the line of cars behind the hearse as it traveled from church to cemetery stretched as far as I could see, a testament to the importance of a quiet, ordinary life. I've never forgotten that sight, and what it showed me about how to live.

this whole piece is actually quite extraordinary. Loved every word, every perfectly honed description. Reminds me of Anne Lamott's essay in this week's WaPo (that's high praise, fyi). Here's to our quotidian days, to devotion and complexity, and to your gift of sharing.